A Few Aztec Riddles

Watching the Hobbit in theatres last weekend got me thinking about riddles. Not only are they amusing, but the figurative language and ideas contained within them can point to interesting tidbits of culture. I’ve pulled a few of my favorites from the Florentine Codex and included them below, in slightly more informal language. After each riddle and its answer I’ve added some of my own notes and interpretations of the concepts they nod to (the commentary is my own work, not that of Anderson and Dibble).

Q: What’s a small blue gourd bowl filled with popcorn?

A: It’s the sky.

Mesoamerican cosmology divides the universe into sky and heavens (topan) above, the earth’s surface like a pancake or tortilla in the middle (tlalticpac), and the underworld (mictlan) below. Though all three have their own distinct and separate characteristics, they interpenetrate to a certain degree, and this riddle hints at that in a playful manner. The gourd itself is a product of the earth and its underworld powers, doubly so as it’s a water-filled plant (and is often likened to the human head), as is popcorn. In fact, first eating corn is the moment where an infant becomes bound to the earth deities as it takes of their bounty and starts to accumulate cold, heavy “earthy-ness” within its being. It’s also the start of a debt to the earth and vegetation gods — as They feed the child, one day that child will die and return to the earth to feed Them. I covered some aspects of this idea in my Human Corn post, if you’re curious to read more.

Q: What’s the little water jar that’s both carried on the head and also knows the land of the dead?

A: The pitcher for drawing water.

The land of the dead is traditionally conceived of as a place dominated by the elements of earth and water, filled with cool, oozy dampness. Rivers, wells, springs, and caves were places where the underworld power was considered to leak through to the mortal realm. Not only did this power seep through to us, but we could sometimes cross through them to reach the underworld as well (the legendary Cincalco cave being one of the most famous of these doors). Thus, thrusting the jar down into a watering hole or a spring, breaking through the fragile watery membrane, was sending it into Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue’s world in a way.

Q: What lies on the ground but points its finger to the sky?

A: The agave plant.

The agave plant, called metl in Nahuatl and commonly referred to as a maguey in the old Spanish sources, is a plant loaded with interesting cultural associations. Its heart and sap is tapped to produce a variety of traditional and modern liquors like pulque, octli, and tequila, linking it to the earth-linked liquor gods like Nappatecuhtli, Mayahuel, and even Xipe Totec and Quetzalcoatl in their pulque god aspects. Additionally, each thick, meaty leaf is tipped with a long black spine that’s much like a natural awl. This spine was one of the piercing devices used by priests and the general public alike to perform autosacrifice and offer blood to the gods. Lastly, the beautiful greenish-blue color of the leaves of some species (like the blue agave), is the special color traditionally associated with beautiful, divine things. Take a look at a photo of the respendent quetzal’s tailfeathers — they’re just about the same color as the agave.

Q: What’s the small mirror in a house made of fir branches?

A: Our eye.

The Aztecs strongly associated mirrors with sight and understanding. Several gods, most notably Tezcatlipoca (the “Smoking Mirror”), possessed special mirrors that would allow them to see and know anything in the world by peering into them. Some of the records we have from before and during the Conquest record that some of the statues of the gods had eyes made of pyrite or obsidian mirrors, causing a worshipper standing before them to see themselves reflected in the god’s gaze. In the present day, some of the tigre (jaguar) boxers in Zitlala and Acatlan wear masks with mirrored eyes, discussed in this post and video. One last point on mirrors — in many of the huehuetlatolli (ancient word speeches), the speaker implores the gods to set their “light and mirror” before someone to guide them, symbolizing counsel, wisdom, and good example. The comparison of eyelashes to fir branches is rather interesting, as it reminds me of the common practice in many festivals of decorating altars with fresh-cut fir branches. The two elements combine to suggest a tiny shrine of enlightenment, the magic mirror nestled in its fragrant altar like a holy icon.

Q: What’s the scarlet macaw in the lead, but the raven following after?

A: The wildfire.

I included this one simply because I thought it was exceptionally creative and clever. I’m pretty sure it would stump even a master riddler like Gollum!

*****

Sahagún, Bernardino , Arthur J. O. Anderson, and Charles E. Dibble. General History of the Things of New Spain: Florentine Codex. Santa Fe, N.M: School of American Research, 1950-1982, Book VI, pp.236-239.

Aztec Art Photostream by Ilhuicamina

Happy New Year’s! Instead of fireworks, let’s ring in the new year with a superb photostream from Flickriver user Ilhuicamina. This set is of exceptional quality and covers many significant artworks excavated from the Templo Mayor and safeguarded by INAH at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Take a look!

Astronomical Alignments at the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan, Mexico

In honor of the spring equinox, I’d like to share an interesting article by Ivan Šprajc that explores some theories regarding possible astronomical associations of the architecture of the Grand Temple. Mr. Šprajc is a Slovenian archaeoastronomy specialist with an interest in the ancient astronomical practices of the Aztec, Maya, and Teotihuacan peoples. This paper, “Astronomical Alignments at the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan, Mexico” is the result of the studies he conducted at the excavation site of the Huey Teocalli in Mexico City.

In this paper, Šprajc agrees with his predecessors Aveni, Calnek, Tichy, and Ponce de Leon that the Templo Mayor was indeed constructed to align with certain astrological phenomena and dates. This initial concept is partially based on some clues recorded by Mendieta that the feast of Tlacaxipehualiztli “fell when the sun was in the middle of Uchilobos [archaic Spanish spelling of Huitzilopochtli].”

The more traditional position, held by Aveni et al and supported by Leonardo López Luján in “The Offerings of the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan” (2006) holds that the festival’s beginning was marked by the perfect alignment of the sunrise between the two sanctuaries atop the Temple on the first day of the veintena according to Sahagun. To wit, Sahagun recorded that the festival month began on March 4/5 (depending on how you correct from the Julian to Gregorian calendar) and ended shortly after the vernal equinox.

Unlike his peers, Šprajc concludes that the festival of Xipe Totec was marked by the sun setting along the axis of the Teocalli. At that time, the sun would seem to vanish as it dropped into the V-shaped notch between the two shrines of Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli. His conclusion partially stems from a slightly different measurement of the orientation of the temple than the other archaeologists, and his preference for Mendieta’s dating of the start and end of Tlacaxipehualiztli, which would start right around the vernal equinox and then end on about April 4th.

Who do I think is correct? I think the jury is still out. Both the sunrises and sunsets were marked by the priests with copal offerings and music, and both were involved in the flow of various festivals, so we know for sure that the scholars and clergy of Tenochtitlan assigned significance to both. Given the issue of varying estimates of how much the Templo Mayor has settled into the soft soil of the remains of Lake Texcoco, and differing theories on how much the structure has warped due to intentional destruction and pressure from the layering of Mexico City on top, and it becomes hard to present a bulletproof argument for either side.

Šprajc presents some additional interesting possibilities for alignments with Mount Tlamacas and Mount Tlaloc nearby, and a potential method of tracking the movement of the sun that possesses regular intervals of 20 days (matching an Aztec month) and 26 days (two Aztec weeks) that are intriguing. However, I generally consider Sahagun more reliable than Mendieta, as his research methods were among the best at the time, and modern study has tended to vindicate his records over those of historians working at a greater remove in time after the Conquest. There’s also the issue that Šprajc seems to be quite outnumbered when it comes to support for his alignment, and some of those who disagree with him, like Leonardo López Luján, have devoted decades of their lives to studying the Templo Mayor specifically. I’d also like to close with the possibility that everyone could be wrong — the tendency to see astronomical alignments under every rock and bush that were never intended by the people they’re studying has plagued archaeology for a very long time, and in the end, it could be the case here as well. Regardless, the debate is interesting and well worth reading, and the journal article contains a number of useful photographs and diagrams of deep within the layers of the Templo Mayor that are rewarding in and of themselves.

To download a full-text PDF copy of the journal article for free from the Inštitut za antropološke in prostorske študije (Institute of Anthropological and Spatial Studies), please click HERE. Alternatively, you can read it on-line at Issuu in simulated book format straight from your web browser by clicking HERE.

As a bonus, I’ve embedded a beautiful video recorded by Psydarketo below. It’s footage of the sun rising and aligning in the central doorway of the sanctuary atop the Mayan temple at Dzibilchaltun on March 20th, 2011 — last year’s spring equinox. It’s a similar technique to what I discussed above at the Templo Mayor, except that the sun is framed in the doorway rather than in the V-shaped space between twin sanctuaries. Close enough to help give a picture of how things would have looked in Tenochtitlan, and wonderful to watch in its own right.

Courtesy link to the original video at Psydarketo’s YouTube page.

————————————————-

WorldCat Citation

Tigre Boxing In Acatlan: Jaguar & Tlaloc Masks

Up today is another video about the Mexican Tigre combat phenomenon I discussed a few weeks ago. This one shows a style of fighting practiced in Acatlan. Instead of rope whip-clubs as in Zitlala, these competitors duel with their fists.

Courtesy link to ArchaeologyTV’s page on YouTube for this Tigre combat video.

A particularly interesting feature of this video is the variety of masks. Not only do you see the jaguar-style masks, but you’ll also see masks with goggle eyes. Goggle eyes are, of course, one of the signature visual characteristics of Tlaloc, the very Teotl this pre-Columbian tradition was originally dedicated to. (And still is in many places, beneath the surface layer of Christian symbols.) If you look closely, you might notice that some of the goggle eyes are mirrored. The researchers behind ArchaeologyTV interviewed one of the combatants, who said that the significance of the mirrors is that you see your own face in the eyes of your opponent, linking the two fighters as they duel.

This idea of a solemn connection between two parties in sacrificial bloodshed was of major importance in many of the pre-Conquest religious practices of the Aztecs. It can be seen most clearly in the gladiatorial sacrifice for Xipe Totec during Tlacaxipehualiztli. During this festival, the victorious warrior would refer to the man he captured in battle as his beloved son, and the captive would refer to the victor as his beloved father. The victim would be leashed to a round stone that formed something of an arena, and given a maquahuitl that had the blades replaced with feathers, while his four opponents were fully-armed. As the captor watched the courageous victim fight to the death in a battle he couldn’t win, he knew that next time, he might be the one giving his life on the stone to sustain the cosmos.

Tigre Rope Fighting In Zitlala

Following up on last week’s post discussing the survival of Precolumbian gladiatorial combat in honor of Tlaloc in Mexico, I’ve got a video today that actually shows part of a Tigre whip match at Zitlala. Now that this activity has come to my attention, it’s something I’ll be watching for videos of in addition to Danza Azteca. It’s interesting getting to actually see the story behind the jaguar mask and contemplate the deeper meaning behind the fighting.

Courtesy link to ArchaeologyTV’s page on YouTube for this Tigre combat video.

In case you’re wondering, the special rope club used by Tigre fighters in Zitlala are called cuertas. The modern cuerta itself is actually a “friendlier” version of heavier rawhide and stone clubs used previously, which in turn were descended from stone and shell clubs used when the battles may well have been lethal. For obvious reasons, the present-day trend has been away from fatal contests, though the underlying meaning of giving of oneself to Tlaloc for a plentiful harvest endures today among those who remember.

Tlaloc In Zitlala

Came across an interesting photograph recently that’s quite interesting, as it shows an aspect of a Pre-Columbian ceremony still surviving today in Zitlala, Mexico.

Tigre Fighter With Whip & Jaguar Mask. Copyright 2008 by the Associated Press/Eduardo Verdugo. Used without permission.

Link to original photograph source.

Original Caption:

“A man dressed as a tiger carries a small whip made from rope in Zitlala, Guerrero state, Mexico, Monday, May 5, 2008. Every year, inhabitants of this town participate in a violent ceremony to ask for a good harvest and plenty of rain, at the end of the ceremony men battle each other with their whips while wearing tiger masks and costumess. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)” [Cehualli’s note — “tiger” is a common mistranslation of “tigre,” when the context makes it apparent a jaguar or other large cat is meant.]

Now…there’s a lot more going on here that the photographer doesn’t get into in his note. Specifically, that this is a modern survival of traditional indigenous religious practices.

Why do I think this? Let me explain.

There’s a certain ancient god of rain in Mesoamerica who has traditionally been associated with jaguars… and that’s Tlaloc. In the codices, if you look carefully you can see that He’s always depicted with long, fearsome jaguar fangs. The growl of the jaguar resembles the rolling of distant thunder, and the dangerous power of such an apex predator fits the moody, explosive-tempered Storm Lord quite nicely. The jaguar as a symbol of Tlaloc is a very ancient tradition that appears across the whole of Central America, whether the god is being called Tlaloc, Cucijo, Dzahui, or Chaac.

The whip-club is another hint. Flogging has been done as part of rain ceremonies for Tlaloc for centuries (I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s symbolic of lightning). Additionally, though the photographer didn’t mention this, one knows what happens when people strike each other hard with whips like the one the man in the photo is shown carrying — you bleed. A lot.

In Prehispanic Mexico, one of the important rituals for Xipe Totec, the Flayed Lord, god of spring and new growth, is called “striping.” Striping involved shooting the sacrificial victim with arrows for the purpose of causing his blood to drip and splash on the dry earth below, symbolizing rain that would bring a good harvest. Similar rituals specifically devoted to Tlaloc were also done, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the gladiatorial combat done for Xipe Totec had the same basic idea in mind, sprinkling blood over the ground done to call the rain.

The next part is due to my good friend Shock and her impressive knack for research. While we were discussing this photo, Shock directed me to an excellent article about this phenomenon known as “Tigre Boxing” that still exists all throughout Mexico today. It even discusses this specific form of battling with whips in Zitlala that this photograph is of. I highly recommend checking it out, as it’s loaded with more information about the surviving practice of gladiatorial combat for rain, complete with many excellent photos of the jaguar masks, sculptures, and even videos of the combat!

Aztecs At The British Museum

In the spirit of the aphorism “a picture is worth a thousand words,” I recommend stopping by the British Museum’s Aztec collection online. They have available 27 photographs (well, 26 if you ignore the crystal skull that’s been proven to be a hoax) of beautiful Aztec and Mixtec artifacts. Among them are statues of Quetzalcoatl, Tezcatlipoca, Mictlantecuhtli, Tlazolteotl, Tlaloc, Xochipilli, and Xipe Totec, as well as a rare mosaic ceremonial shield, a turquoise serpent pectoral, and a sacrificial knife. The images are thought-provoking and intense, as these objects speak wordlessly the vision of the Nahua peoples without Colonial censorship.

Click HERE to visit the British Museum’s Aztec Highlights.

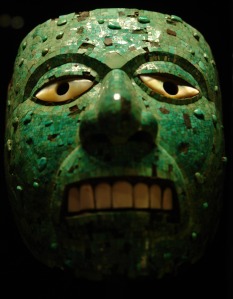

As a bonus, I located an excellent photograph of a jade mask of Xiuhtecuhtli, God of Time and Fire, which is a part of the British Museum’s collection but is not on their website. Thank you Z-m-k for putting your fine photography skills to work on this worthy subject material and for your kindness in sharing it under the Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 2.5 License.

Update: Five New Hymns in “Hymns & Prayers”

I’ve been busy over the past several days scouring the Web for English translations of more hymns, especially more modern ones than the public domain Rig Veda Americanus that you can download. And I’ve had some good luck with this, amazingly enough. There are now hymns to the Sun, Huitzilopochtli, Xipe Totec, Cihuacoatl, and Chicomecoatl that you can read! I recommend swinging by the Hymns & Prayers page to see the new songs. Please note that they’ve visible via Google Book Search’s Limited Preview function, and follow the special orange-highlighted instructions in each entry on how to pull up those specific pages that have the songs. I’ve found another source of a truckload more hymns that I’ll be adding in the next few days, but I’ve got to get the complete list of desired pages for that one hashed out before I can add it. So… watch for another Update notice when that one goes up.

In other update news, I straightened out some links and added some new ones over in the History sections. I also finished off Huitzilopochtli’s little page in the section of The Gods, including adding a snapshot of Him as depicted in the Codex Borbonicus.

Oh, and I also found a real gem — a public domain PDF of the commentary on the Codex Fejéváry-Mayer by significant Mesoamericanist Dr. Eduard Seler. It’s even in English, too! That’s over in the Codices subsection of Sacred Texts.

So if you haven’t browsed through the static pages of this blog in a few days, you might want to swing by and check out the new stuff!

April 18, 2008 | Categories: Culture, Literature, Miscellaneous, Religion, Updates | Tags: adorar, antes de la conquista, Aztec, Aztec religion, Azteca, ética, belief, ceremony, Chicomecoatl, Cihuacoatl, Codex, Codex Borbonicus, Codex Fejéváry-Mayer, codice, commentary, costumbre, creencia, cultura, culture, dios, Eduard Seler, ethics, faith, fe, filosofía, god, goddess, gods, Huitzilopochtli, idea, indígena, Indian, indigenous, indio, la religión de los aztecas, Mesoamerica, Mexica, Mexicayotl, Mexico, moral, morality, Nahua, philosophy, pre-Columbian, pre-Conquest, Pre-Hispanic, Precolumbian, preconquest, Prehispanic, reflexión, religion, Rig Veda Americanus, Sacred Texts, Sun, teología, Teotl, theology, thought, Tonatiuh, tradicional, traditional, update, worship, Xipe Totec | 2 Comments