That Is Not Dead Which Can Eternal Lie

In honor of the springtime finally rolling around after this seemingly-endless winter, I’d like to introduce you to a mysterious creature which the Aztecs said dies and rises with the seasons.

“In the winter, it hibernates. It inserts its bill in a tree; [hanging] there it shrinks, shrivels, molts. And when [the tree] rejuvenates, when the sun warms, when the tree sprouts, when it leafs out, at this time [it] also grows feathers once again. And when it thunders for rain, at that time it awakens, moves, comes to life.”

What is this mysterious creature that defies death?

It’s the hummingbird (huitzitzili in Nahuatl).

Incidentally, remember that the hummingbird is Huitzilopochtli’s symbol, and note that many hummingbirds, including several species in Mexico, have the brilliant blue-green color of divinity for their plumage, just like another sacred bird, the resplendent quetzal. These feathers, believed to have been shed like dead leaves in the fall, are linked to fresh, living plants by Sahagun’s informant, called into existence after the warmth of the sun, power of the sky gods, works in tandem with the watery might of Tlaloc and the other earth and vegetation gods, spiraling together to burst forth in life and movement. Thus, a bird that’s possibly the perfect representation of the sky with its ability to hover and move at will in the air, shows its other face as a facet of the earth/water/plant divinity complex, a deity web that also extends into the realm of the dead. Thus, this tiny little winged jewel is a microcosm of the vast world around it and the deities interwoven in the system.

“Canto del Colibri,” courtesy of jjeess11

*****

Sahagún, Bernardino , Arthur J. O. Anderson, and Charles E. Dibble. General History of the Things of New Spain: Florentine Codex. Santa Fe, N.M: School of American Research, 1950-1982, Book XI, pp.24.

Alarcón: Prayers For Protection From Evil While Sleeping

Among the populace of the Aztec empire, the line between religion and magic often blurred in day to day life. While the priestly class held a great amount of power in mediating between the people and the gods, and by extension had a powerful influence on directing orthodoxy, folk practices flourished within the family household. One of these was the practice of offering prayers and desirable substances (often copal incense, tobacco, and sometimes blood) to the lesser spiritual beings inhabiting everything from the trees to the crops to the tools by which people lived. While these animistic entities were less grand than the mighty cosmic lords like Huitzilopochtli and Quetzalcoatl, with their broad power over the universe and the state, these local spirits had their own gifts. This influence carried extra weight for the humble individual due to its intimate proximity — while Tezcatlipoca’s wrath could lay waste to the entire kingdom, the fury of a small farmer’s sole cornfield could prove just as deadly for that individual as his livelihood dried up.

In this post, I’ll share with you a set of three of these short folk prayer-spells, collected by the inquisitor Hernando Ruiz de Alarcón in his “Treatise on Heathen Superstitions” in the early 17th century. These incantations were intended to guard a sleeper against evildoers invading his or her home in the night, and to express gratitude in the morning for a safe rest. Note that the supplicant in these prayers is actually praying to the spirits of their bed and their pillow, rather than a more familiar high god like Tlaloc. Incantations are quoted from the excellent English translation of Alarcón by J. Richard Andrews and Ross Hassig. Incidentally, if you can read Spanish, I found a full text copy of the Paso y Tronsco fascimile online at the Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, viewable by clicking HERE. Commentary about each prayer is my own material.

Let it be soon, O my jaguar mat, you who lie opening your mouth toward the four directions. You are very thirsty and also hungry. And already the villain who makes fun of people, the one who is a madman, is coming. What is it that he will do to me? Am I not a pauper? I am a worthless person. Do I not go around suffering poverty in the world?

The supplicant here calls upon his bed (“jaguar mat”), a mat made of reeds and palm fronds to protect him from the nocturnal sorcerer, the nahual. This particular flavor of witch was greatly feared throughout the region due to his ability to control minds, paralyze, and shapeshift. He was believed to often indulge in robbery like a cat burglar, breaking into homes in the dead of night to bewitch and rob his prey. Sometimes, he would violate and kill his victims. Interestingly, Quetzalcoatl was noted by Sahagún in the Florentine Codex to be the patron of this supernatural lawbreaker.

The structure of this prayer is double-layered — the supplicant begins with calling on the spirit of his bed to protect him, but then shifts to make a declaration of his extreme poverty and worthlessness as a robbery target. Perhaps he had in mind a subtle defense here — rather than asking the spirit to try to destroy or disempower the witch, which might be unlikely to work as they were considered to be quite strong, he’s asking it to trick the burglar by convincing him that there’s nothing of value in this house, better go somewhere else.

The bed itself is described in an interesting way. It reaches out towards the four directions, thus anchoring it very firmly in physical space, but also possibly linking it to the greater spiritual ecosystem, as a common verbal formula of invoking the whole community of the divine is to call to all the directions and present them with offerings. It also reminds me of the surface of the earth (tlalticpac) which similarly fans out as a flat plane towards the cardinal directions, making the bed a tiny replica of the earthly world. The reference to gaping mouths, hunger, and thirst acknowledges that the spirit of the bed has its own needs and implies that the speaker will attend to them. In the Aztec world, nothing’s free, and a favor requested is a favor that will have to be paid for. Alarcón doesn’t note what offering is given to the mat here, but in other invocations of household objects recorded in the book, tobacco and copal smoke come up repeatedly.

Let it be soon, O my jaguar seat, O you who are wide-mouthed towards the four directions. Already you are very thirsty and also hungry.

This prayer is the companion of the one discussed above, except directed to the sleeper’s pillow (the “jaguar seat”). Incidentally, you might be wondering why these two objects are named “jaguar.” Andrews and Hassig speculate in their commentary that it may have been inspired by the mottled appearance of the reeds making up the bedding. I think it may be a way of acknowledging that these simple, seemingly-mundane objects house a deeper, supernatural power. The jaguar is a creature of the earth, of the night, and sorcery in Mesoamerican thinking, and in particular is a symbol of Tezcatlipoca. It doesn’t seem like a coincidence to me that a nocturnal symbol is linked to things so intimately tied to sleep and being interacted with in the context of their magical power. The adjective “jaguar” also appears elsewhere in Aztec furniture as the “jaguar seat” of the kings and nobles, which is often used as a symbol of lordly authority. The gods themselves are sometimes drawn sitting on these jaguar thrones, including in the Codex Borbonicus (click to view). Once again, another possible link to ideas of supernatural power and rulership — authority invoked to control another supernatural actor, the dangerous witch.

O my jaguar mat, did the villain perhaps come or not? Was he perhaps able to arrive? Was he perhaps able to arrive right up to my blanket? Did he perhaps raise it, lift it up?

This final incantation was to be recited when the sleeper awoke safely. He muses about what might have happened while he slumbered. Maybe nothing happened… or maybe a robber tried to attack, coming so close as to peek under the blanket at the defenseless sleeper, but was turned away successfully by the guardian spirits invoked the previous night. Either way, the speaker is safe and sound in the rosy light of dawn, alive to begin another day.

*****

Ruiz, . A. H., Andrews, J. R., & Hassig, R. (1984). Treatise on the heathen superstitions that today live among the Indians native to this New Spain, 1629. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp.81-82

Aztec Art Photostream by Ilhuicamina

Happy New Year’s! Instead of fireworks, let’s ring in the new year with a superb photostream from Flickriver user Ilhuicamina. This set is of exceptional quality and covers many significant artworks excavated from the Templo Mayor and safeguarded by INAH at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Take a look!

Quiquiztli: The Conch Shell Trumpet

It’s the ending of the old baktun and the dawning of a new one, and I’d like to greet both the new era and the return of the Sun on this Winter Solstice with the blowing of conch horns!

The Aztecs named the conch shell trumpet quiquiztli, and the musicians who played them “quiquizoani.” This is the instrument that Quetzalcoatl played to defeat the devious challenge of Mictlantecuhtli, the Lord of the Dead, and reclaim the ancestral bones of humanity at the start of the Fifth Sun. I have seen some speculation that the “mighty breath” blown by the Plumed Serpent to set that newborn Sun moving in the sky was actually a tremendous blast on a conch horn. It’s the trumpet the priests played to call their colleagues to offer blood four (or five) times a night in the ceremony of tlatlapitzaliztli, and also during the offering of incense, according to Sahagun in the Florentine Codex . Tecciztecatl, the male Moon God, is sometimes depicted emerging from the mouth of a quiquiztli. The sound of the instrument itself was considered by the Aztecs to be the musical analog to the roar of the jaguar. Like the twisting spiral within the shell, the associations are nearly endless, doubling back on each other in folds of life, death, night, dawn, and breath.

The quiquiztli appeared in two offerings at the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan (offering #88). One shell was found on Tlaloc the Rain Lord’s side (not at all surprising, given the overwhelming watery connotations of the instrument). A second one was found on Huitzilopochtli’s side of the manmade replica of Coatepetl. If you would like to actually hear one of these very trumpets being played, you can click HERE to visit the International Study Group on Music Archaeology’s page for these trumpets. You can directly download the MP3 recording by clicking HERE.

I also found a beautiful photograph of an Aztec or Mixtec conch trumpet (covered in intricate carvings) currently in the holdings of the Museum of Fine Arts here in Boston. If you’d like to view the photo and see their notes on the artifact, please click HERE. If you’d rather jump right to the full-size, more detailed image, click HERE instead.

Want to learn more about the trumpet and its uses in Mesoamerican cultures past and present? Head on over to Mixcoacalli and read Arnd Adje Both’s excellent 2004 journal article called “Shell Trumpets in Mesoamerica: Music-Archaeological Evidence and Living Tradition” (downloadable full text PDF). It gives a valuable introduction to the instrument in Teotihuacan, Aztec, and Mayan societies and includes numerous interesting photos and line sketches as a bonus. I couldn’t find a direct link to the article on his site, but I did find it on his server via Google. As a courtesy, the link to his homepage is here. There is some other interesting material relating to the study of ancient Mesoamerican music on there, so I recommend poking around.

What about South American cultures? I’m a step ahead of you — why not go here to read an interesting article on Wired about a cache of 3,000 year old pre-Incan shell trumpets found in Chavin, Peru? Includes recordings and photos.

Finally, if you’re curious for an idea of how the Aztecs and Maya actually played the quiquiztli, including how they changed the tone of the instrument without any finger-holes or other devices, you can view a demonstration by ethnomusicologist John Burkhalter below. If you noticed that the trumpeter in the codex image I embedded earlier has his hand slipped into the shell, you’ll get to see what that actually does when the horn is played in the video.

Xultún And The Baktun

In honor of the approaching end of the 13th baktun on December 21, per the famous Mayan calendar, I’d like to write about a piece of ironclad historical evidence contradicting the “Mayan doomsday” nonsense. That particular piece of evidence lies in the ruins of Xultun.

Xultun was once a flourishing Mayan metropolis, and its importance continues to the present day as the site of a series of murals of great significance to clearing up an archaic misunderstanding of the great calendar. More specifically, painted on the walls in a house that appears to have been a workshop for scribes and astronomers, is a series of complex astronomical tables extending well past the end of 2012. In other words, the Mayan astronomers of the ninth century C.E. most certainly didn’t think the world would end when the thirteenth baktun did, but instead carried on with their work charting planetary and stellar activities well beyond the supposed end of the world. “So much for the supposed end of the world,” quips William Saturno, one of the present-day (re) discoverers of these scientific calculations.

Another of Saturno’s comments sums up the contrast between Western pop culture’s misconceptions and Mayan thought nicely, in my opinion — “We keep looking for endings… the Maya were looking for a guarantee that nothing would change. It’s an entirely different mindset.” (National Geographic, 5/10/2012)

After the above excerpts, you might be interested in getting a look at Xultun and these murals for yourself. If so, you’re in luck!

If you click HERE, you can view National Geographic’s “Giga Pan” high resolution photographs of some of the murals.

If you’d like to explore the beautiful stone stelae (carvings) that dot the city, you can click HERE to visit the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard’s website cataloguing a bit of the site’s history, its carvings, and their locations around the town. (The diagrams of the carvings are in the list on the lefthand side of the page.)

Finally, National Geographic has also prepared a short video on the discoveries at Xultun for your viewing pleasure, which you can view HERE if you have trouble viewing the embedded version below.

Conquistador Helm In Salem, MA Part 2

A quick post today to follow up on my last one. I was digging through a disc of photos my father took while we were visiting Salem, and it turns out he also snagged a shot of the conquistador’s helmet. He had a proper DSLR camera with him and was able to get a larger, higher resolution photo of the helm, so I’m posting it too so you can get a more detailed look. As always, click to view the image in its full size.

Conquistador Helm In Salem, MA

Earlier this month I visited the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, MA and spotted a surprising object in their collection. Amidst the lovely array of East Asian artwork (better than the MFA’s holdings in Boston proper, in my opinion), nautical paintings and artifacts, and other marvels, sitting unobtrusively on a shelf in their gallery devoted to curios collected by local sailors from around the world, sits a conquistador’s helmet. I snapped a couple of photos to share with you all (please excuse the quality, I wasn’t planning on doing any photography and flashes were forbidden in the museum to boot). Click to view the photos full size.

First, a shot of the whole helmet on its shelf.

Next, a close-up of the antique paper label pasted on the helm by a museum curator (presumably) a long time ago. Judging by the paper, ink, and handwriting style, I’m guessing it was attached to the artifact sometime in the 19th century. The label reads “An Ancient Spanish H[elmet] found in Mexico, and probably [worn?] by some of the followers of Cortez.”

Aztecs In The Werner Forman Archive

Tonight I’ve decided to bring your attention to a major collection of photographs of Aztec and other Mesoamerican art, crafts, and architecture. It’s housed at the Werner Forman Archive in the United Kingdom. It’s a treasure trove of wonderful pictures of literally thousands of different objects and places around the world, including pictures relating to the Aztecs, Maya, Teotihuacanos, and other peoples of Central America.

Click HERE to enter the Archive and begin browsing or searching.

You can browse their Precolumbian section for photos covering both North and South American peoples, or you can try searching for Aztec, Maya, or more specific keywords. To give you a hint at how much there is to explore, the full Precolumbian section has 763 photos available online!

As they don’t appear to look kindly on people rehosting their images, and hotlinking is rude, I’ll just drop a few direct links here to some particularly interesting photos to get you started…

Click here to see a sculpture of Tlaloc, Lord of Storms and Tlalocan, in His Earth-lord guise.

Want to see a pectoral device in the shape of a chimalli (shield)?

How about Quetzalcoatl’s signature necklace, the wind jewel?

Aztec Weaponry Demonstration – Discovery Channel

Today I’d like to share a video clip I came across that shows a portion of a Discovery Channel special. In it, they explore effectiveness of several traditional Aztec weapons and compare them to their closest Spanish analogues. Most interesting are the sequences where they demonstrate the obsidian-bladed sword-club, the maquahuitl (also spelled macuahuitl) and the sling. A particularly nice little surprise about this episode is that Dr. Frances Berdan speaks a bit about the maquahuitl. If you’re wondering why I’m highlighting that, it’s because she’s a significant scholar of Mesoamerican studies. What has she done for you lately, you ask? Well, you might want to thank her and Dr. Anawalt for the current definitive edition of the Codex Mendoza, for starters.

That aside, enjoy the video!

Two Aztec Censer Photos

While browsing links and foraging for data, I came across an excellent pair of photos on Flickr that tie in nicely with yesterday’s post on pre-Conquest Aztec censers. Both photographs were taken by Lin Mei in 2006 at the Museo del Templo Mayor (Museum of the Grand Temple) and adjacent excavation site of the Huey Teocalli itself in Mexico City. They are hosted on Rightstream’s Flickr photostream as a part of his Templo Mayor set of images. I recommend taking a look at the full set in addition to the two I’m highlighting here, as the photos are very good quality and provide a good look at many of the fascinating examples of Mexica art and architecture uncovered by the Templo Mayor archaeology team. My thanks to Leo and Lin Mei for generously allowing their work to be shared under a Creative Commons 2.0 license.

The first photo is a beautiful example of a ladle-type censer, intended to be carried in the hand and used to incense places, people, sacred images, etc. It’s the design Walter Hough described as being derived from a basic tripod incense burner design, where one leg is elongated into a handle, producing a ladle form.

Image 055 in Rightstream’s Flickr photostream, photograph taken by Lin Mei in 2006

Used under a Creative Commons 2.0 License

The second image is a picture of the large, stationary stone brazier Hough described as being used for burning incense, offerings, ritual implements and paraphernalia, and as vessels for sacred temple fires that were never allowed to go out. The popochcomitl in the photo below is beautifully preserved, and a great amount of sharp, clear detail is apparent. Look closely at the narrow waist of the hourglass shape, and you’ll see the belt-like knotted bow I discussed yesterday. It’s a much better example than the grainy turn of the century photograph available in the linked article. You’ll also notice a beautiful monolithic serpent head nestled between the two braziers. The alternating brazier – serpent – brazier pattern continues over large sections of the stepped pyramid. It’s a logical motif when one remembers that the Grand Temple, at least on the southern side where Huitzilopochtli’s sanctuary was, is a man-made replica of the Coatepetl (Snake Mountain) where Huitzilopochtli was born and defeated the jealous Southern Stars. If you’d like to read that story, you can click HERE for my retelling of that exciting narrative.

Image 001 in Rightstream’s Flickr photostream, photograph taken by Lin Mei in 2006

Censers and Incense of Mexico and Central America

While doing some research on different types of censers (incense burners) used in Mesoamerica, I came across a useful article on the subject by Walter Hough, entitled (creatively) “Censers and Incense of Mexico and Central America.” The article dates from 1912 and doesn’t have the benefit of recent excavations at the Huey Teocalli in Mexico City, but I still found it valuable as a solid overview of the major types of incense burners (popochcomitl in Nahuatl) used in precolumbian Mexico and neighboring regions. It’s a well-organized and reasonably-concise article, and contains a good number of photographs of examples for each of the major shapes and style variations by broad ethnic groupings. To read “Censers and Incense of Mexico and Central America” by Walter Hough via GoogleBooks, please click HERE. A full-text PDF of the article can also be downloaded, as the article is in the public domain. (A warning note — unsurprisingly, given its age, Hough’s article is marred by some obnoxious ethnocentric language common to writing from the period. Fortunately, it’s less pervasive than what I’ve seen from some of his contemporaries, so hopefully you can look past it to benefit from the real meat of the essay.)

I’d like to comment briefly on some of the most interesting parts of the article. I’ll start with some thoughts about the large, stationary “hourglass” type censer he mentions, which were permanent installations at the temples (depicted on page 9 of the PDF, page 112 in the original numbering). Called tlexictli, or “fire navels,” they instantly bring to mind Xiuhtecuhtli (also called Huehueteotl), the ancient Lord of Fire, who is said to dwell in the “navel” of the universe, as recorded throughout the Florentine Codex by Sahagun. Also according to Sahagun, these large braziers provided not only continual light, warmth, and a place to burn copal, but were used in the disposal of some offerings and ritual implements. The objects to be cremated were burned in a tlexictli, and then the ashes were buried at certain holy sites on the edge of bodies of water (Hough, PDF p.11). It’s a fascinating variation on the theme of water meets fire that pervades traditional Aztec thought, here manifesting in a team effort of the two opposing forces in destroying sanctified objects that are due to leave the physical world for the spiritual realm.

Staying on the subject of the tlexictli a moment longer, I’d like to call your attention to the photo on page 44 of the PDF, which shows one of the “fire navel” braziers. Around the narrow waist of the censer is a knotted bow. These bows frequently show up in Aztec art, either tied around objects that are being offered or tied around people, animals, or gods. Quetzalcoatl is often shown in the codices with these bows tied around his knees and elbows, such as in plate 56 of the Codex Borgia. Mictlantecuhtli is wearing the pleated paper bows around his joints as well. To my knowledge, we don’t yet fully understand the complex meaning behind these bows, but they’re definitely associated with priestly activity and sacrifice. In that light, it seems appropriate to see these bows appear on the tlexictli.

Moving on to more familiar territory, Hough’s paper covers the ladle-type censer commonly depicted in the hands of priests offering incense in the codices, as discussed in my earlier post on the subject of daily copal offerings by the clergy. In his scheme of classification, it is labeled as a type of “gesture”popochcomitl, so called because it’s intended to be held in the hand and used in various motions during ceremony to direct the sweet smoke towards its intended recipient(s). According to the author, this ladle-like shape is a signature of gesture censers among the Nahua peoples, and isn’t as prevalent among groups to the north and south of Central Mexico. This seems to be reflected in the surviving codices, as the majority of the examples I can recall offhand are that shape. I’ve seen a few examples of a bowl-shaped vessel with copal in it as well in the ancient books, which may match the small bowl-type censers he notes as being universal across Mesoamerica.

Gesture censers in varying shapes were used outside of temple activities, as Sahagun notes that the duty to offer copal was shared by everyone in the Aztec empire, which Hough comments on in the household context a bit. Sahagun also recorded that copal was offered before performances of song and dance at the houses of the nobles, which presumably involved small censers that could be manipulated with a hand in at least some cases. I mention that possibility because it’s a custom still widely in use today, as seen among the danza Azteca groups around the world, and one that I can show you as I wrap up today’s post.

The video below is a recording of a dance for Tonatiuh, the Sun, and the dancers have several goblet-shaped censers that they use to offer copal smoke to the four directions. Once the offering is finished, they place the censers back among the other objects of the dance altar spread out on the ground, letting the copal continue to burn and smoke as they dance. Thanks go to Omeyocanze for posting this lovely video.

Courtesy link to Omeyocanze’s page on YouTube for this danza video.

———————————————

*Apologies for not having the citations for Sahagun’s Florentine Codex in just yet, but it’s quite late and I must call it a night before getting up for work later. I’ll add them in when I get the chance soon.

Soustelle’s Daily Life Of The Aztecs

I was doing some digging online today, and had quite a stroke of good luck — I found a complete copy of Jacques Soustelle’s classic The Daily Life of the Aztecs online! The English edition of the entire book is available to read for free on Questia. Soustelle was a famous French anthropologist who specialized in studying the Aztecs before the Conquest, one of the bright lights in Mesoamerican studies of the mid 20th Century. His Daily Life of the Aztecs is one of his best-known works on this subject, covering a wide variety of details of Mexica life in great Tenochtitlan, ranging from architecture to agriculture, religion, economics, and the conduct of war. Though somewhat dated (written in 1962), most of the information in this book still remains quite useful, and his respectful, non-sensationalistic tone is refreshing. As it predates the rediscovery of the Templo Mayor (Huey Teocalli) in the 1970’s, it sadly doesn’t include much on that famous structure. Still, I strongly recommend giving it a read, as it remains one of the better general histories and anthropological overviews of life in Precolumbian Mexico.

Go HERE to read The Daily Life of the Aztecs in full!

Incidentally, I have now activated the Pre-Conquest History page in the History section of this blog’s static pages and placed an additional permanent link to this book there.

Aztecs At The British Museum

In the spirit of the aphorism “a picture is worth a thousand words,” I recommend stopping by the British Museum’s Aztec collection online. They have available 27 photographs (well, 26 if you ignore the crystal skull that’s been proven to be a hoax) of beautiful Aztec and Mixtec artifacts. Among them are statues of Quetzalcoatl, Tezcatlipoca, Mictlantecuhtli, Tlazolteotl, Tlaloc, Xochipilli, and Xipe Totec, as well as a rare mosaic ceremonial shield, a turquoise serpent pectoral, and a sacrificial knife. The images are thought-provoking and intense, as these objects speak wordlessly the vision of the Nahua peoples without Colonial censorship.

Click HERE to visit the British Museum’s Aztec Highlights.

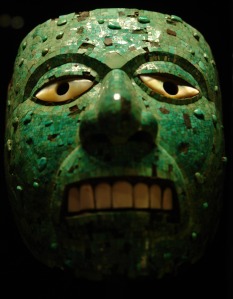

As a bonus, I located an excellent photograph of a jade mask of Xiuhtecuhtli, God of Time and Fire, which is a part of the British Museum’s collection but is not on their website. Thank you Z-m-k for putting your fine photography skills to work on this worthy subject material and for your kindness in sharing it under the Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 2.5 License.

Identity Of The Fire Drill Constellation

Good news! My dear friend Shock answered my plea for help regarding the identity of the Fire Drill constellation that was discussed in my article on greeting the dusk. She’s studied the scholarship on Mesoamerican archaeoastronomy extensively and kindly popped in to shed some light on this issue. This is what she had to say regarding the identity of the Fire Drill:

“Anyway… About the fire drill constellation. It’s Orion’s Belt, clear as day if you look at the evidence. The Pleiades couldn’t possibly be it. It’s a seven/six star cluster within Taurus and used as a reference point for the Fire Drill in the primary source material. Taurus itself couldn’t be it for these same reasons and the fact that its other noticeable stars aren’t in a straight line. The Cygnus idea makes little to no sense considering that Sahagun clearly states in book 7 of the Florentine that the constellation is near the Pleiades. Cygnus is NOWHERE near the Pleiades in the night’s sky. In book 7, look up two parts. First, the fire drill part in Nahuatl and then Sahagun’s commentary in Spanish under Castor and Pollux. Several things are clear; the Fire Drill needs to be by Gemnini and it needs to be by Taurus. It also has to be a straight line of three bright stars. The straightness is reiterated in the Nahuatl text numerous times. And what’s right by both of these, with three bright stars? Orion’s belt. And then you have the comparative ethnography stuff from FAMSI, plus there’s more stuff similar to that which is closer to Mesoamerica.”

So, it does look like the best candidate for the Fire Drill constellation is the stars of Orion’s Belt!

Also, apparently the guy who favors the Northern Cross as the Fire Drill is a poor-quality “scholar” associated with the atrocious “mayalords.org” site, so I’d recommend ignoring him beyond the value of knowing what the crap arguments are out there.

Thanks Shock!

Incidentally, I have updated my other post with this important information for convenience and clarity.

Greeting The Dusk

“Yohualtecuhtli, the Lord of the Night, Yacahuitzli, has arrived! How will his labor go? How will the night pass and the dawn come?”

Following up on my earlier article on how the priests greeted the dawn, above is my rendition of the traditional prayer saluting the dusk. It is a modernized composite of the two variants recorded by Sahagun and Tezozomoc. (To read Dr. Seler’s translation of the Tezozomoc version, click HERE and search within the book for youaltecutli. The only hit is on page 357, containing the prayer in question.)

This prayer was traditionally offered around sundown, as a particular constellation called mamalhuaztli, the Fire Drill, rose from the east into the darkening sky. It was accompanied by the offering of incense, being another one of the nine times a day the priests would offer copal to the Teteo.

You may be wondering exactly what constellation mamalhuaztli is, as its rise was the traditional signal to perform this rite. The bad news is. . . we’re not sure. Partially because the records suck, partially because the constellations have drifted in the sky over the past millennium or so. We have enough information to know that this constellation was in the vicinity of the Pleiades, and apparently some scholars think the Fire Drill was three stars that are part of them. However, the stars in Orion’s belt are another popular theory, and at least one guy seems to consider the Northern Cross a candidate, though his credentials are suspect at best. The link above to the original language of the prayer includes some of Seler’s deductions regarding the identity of this constellation, though sadly the whole thing isn’t available. Go HERE for a very brief discussion on the Aztlan mailing list hosted by FAMSI regarding the Orion vs. Northern Cross debate if you’re curious.

Due to this uncertainty, I’d advise taking the obvious route of observing this prayer either at sunset or right at full dark. It’s not perfect, but it should be in the ballpark I’d think, and archaeoastronomy isn’t my strength. So, good enough for me, and it seems a reasonable alternative for modern practice in the face of a gap in our knowledge. However, if anyone does have a good background in this branch of astronomy and can help out, I’d be interested in hearing what you have to say about the identity of the Fire Drill constellation.

UPDATE 10/2/08:

Well, my dear friend Shock answered my plea for archaeoastronomy help on this issue! This subject is one that’s close to her heart, and she’s studied the scholarship on this area extensively. This is what she had to say regarding the identity of the Fire Drill:

“Anyway… About the fire drill constellation. It’s Orion’s Belt, clear as day if you look at the evidence. The Pleiades couldn’t possibly be it. It’s a seven/six star cluster within Taurus and used as a reference point for the Fire Drill in the primary source material. Taurus itself couldn’t be it for these same reasons and the fact that its other noticeable stars aren’t in a straight line. The Cygnus idea makes little to no sense considering that Sahagun clearly states in book 7 of the Florentine that the constellation is near the Pleiades. Cygnus is NOWHERE near the Pleiades in the night’s sky. In book 7, look up two parts. First, the fire drill part in Nahuatl and then Sahagun’s commentary in Spanish under Castor and Pollux. Several things are clear; the Fire Drill needs to be by Gemnini and it needs to be by Taurus. It also has to be a straight line of three bright stars. The straightness is reiterated in the Nahuatl text numerous times. And what’s right by both of these, with three bright stars? Orion’s belt. And then you have the comparative ethnography stuff from FAMSI, plus there’s more stuff similar to that which is closer to Mesoamerica.”

So, it does look like the best candidate for the Fire Drill constellation is the stars of Orion’s Belt!

Also, I’ve been informed that the guy who favors the Northern Cross as the Fire Drill is a third-rate “scholar” connected to the godawful “Mayalords” site, so I’d recommend ignoring him beyond the value of knowing what the crap arguments are out there.

Thanks Shock!

If you’re particularly interested in this subject, I recommend watching the Comments on this post for more.

Maquahuitl

A quick update today — I came across a link to an interesting little website devoted to the study of the Aztec sword-club, the macuahuitl (also spelled maquahuitl). They even have a new forum for people to discuss traditional Mesoamerican weapons. Cool. Click to visit Maquahuitl, and tell ’em Cehualli sent you. <g>

Templo Mayor: Offering #126

Shock kindly shared the link to this story with me recently, and I thought I would highlight it here as an interesting archaeological discovery. I look forward to when they publish their full findings.

Most Important Offering in Past 30 Years Discovered in Great Temple

Presidencia de la República

go to original

Mexico City – President Felipe Calderón toured the House of the Bows and Bells of the Great Temple Archaeological Zone, where the largest, most important offerings recorded in 30 years of excavations in this zone were recently discovered…