The Rise Of The Eagle

One of the core cycles of myth belonging to the Aztecs is the multipart epic of how they went from their humble beginning as an obscure band of nomads to the lords of Tenochtitlan and the founders of a great empire, all under Huitzilopochtli’s watchful eye. In honor of the festival months of Quecholli (beginning today) and Panquetzaliztli, the veintanas celebrating the Chichimec past and the god who led them to glory, I will be kicking off a special storytelling event. Over the course of November and first week of December, I will be retelling the highlights of the series of legends that comprise this important saga of the Mexica-Tenochca people.

The basic timeline of the Foundation Cycle starts with the big entrance of Huitzilopochtli onto the scene with the Battle of Coatepec. I’ve already posted that one, and I recommend checking it out if you haven’t read it yet, as it sets the stage for things to come.

Once Huitzilopochtli’s arrived, He picks out the Mexica as His own favorite tribe and calls them to leave their ancestral homelands in the north and begin their migration south, deep into the Anahuac Valley. He promises to guard them and guide them to a new home, a place where they will found a mighty empire. They trust in Him and head out, overcoming both human and divine opponents until they eventually reach the place where the eagle perches on the nopal cactus, eating a heart — the sign that they have finally found their new home… Tenochtitlan.

Stay tuned!

How To Make An Incense Stove

I’m in a “How To” mood tonight. You may have noticed copal comes up a lot on this blog, and been interested in experiencing it yourself, but don’t have a place you can burn it with charcoal due to smoke or fire hazard. What to do? Well, I had the same issue myself, and came up with a quick and dirty incense stove design that charcoal-free and smokeless when used. For those who want to give it a try, I thought I’d finally upload photos and some crappy MS Paint blueprints.

Sure, you can buy premade stoves and that guarantees the product doesn’t suck, but they’re not always cheap, and I’ve never seen one that I liked. Building your own can be done for like $5, even less if you are good at scavenging stuff, and you can make it look like you want. Mine is made with a heavy black marble jar that’s quite pretty, and completely hides the jury-rigged wire holder and foil cup hanging inside. When it’s in use, you just see the glow of the hidden candleflame gleaming on the lip, and the incense vapor rising out of the top.

Obligatory Disclaimer/Warning:

Incense stoves get hot and involve fire. This makes them DANGEROUS. Be VERY careful when building and using your stove, as you can burn yourself, your stuff, your pets, etc. if something goes wrong. These blueprints are only a very rough outline of how I built my own stove and are not intended to be professional instructions on how to build incense stoves. There is no associated guarantee of workmanlike quality, fitness for a particular purpose, or safety in either the blueprints or in the end product if you choose to build a stove after looking at these images. It can’t be guaranteed 100% safe, it involves an open flame. Basically, if you start a fire and hurt yourself/others/property, I am not responsible. You’ve been warned.

Materials Needed:

- 1 Container — This can be a jar, a soup can, basically anything with an open top that won’t burn. Theoretically, you could even just have an open frame made of wire or something that would support the incense cup, though that would be pretty ugly. It needs to be wide enough to hold the candle, and shallow enough to allow enough air to sustain the flame. Remember, copal vapor is heavy and will sink, and it can smother a small flame if it gets trapped densely enough around it.

- 1 Piece of Wire — A length of thin wire, about 6 inches long. I used copper as it tolerates heat well and was what I had available, though brass would also be an excellent choice. Whatever wire you use, it needs to be flexible enough to easily twist and bend, but strong enough to support its own weight and the weight of a nugget of copal in the foil cup.

- 1 Sheet of Aluminum Foil — This will be folded into the cup where the resin nugget will go. You’ll want a roughly a 3 inch by 3 inch square if you want to make the cup single-layered, which will maximize the heat transferred to the incense, increasing the strength of the scent.

- 1 Candle — A small candle, preferably a tealight or votive candle. Must be unscented, or you’ll have its smell dueling with the scent of copal. Disgusting. Need unscented tealights? Check Bed Bath & Beyond, I’ve seen huge bags of 100 for about $5. I’ve seen them in CVS convenience stores here in Boston in the bulk bags too, weirdly enough.

- Insulating/Supporting Material — Sand, rocks, the shell of a spent tealight candle, anything that won’t burn and can support the weight of a candle on top. You need to put this under the candle both to protect the surface below it from the heat and to adjust the candle’s height.

Blueprints:

Here are the rough diagrams for building an incense stove like mine, with my notes on the process included in the graphic. +1 for crappy MS Paint drawings…

Photos:

Finally, since making the cup and the wire holder for the cup are the hard part, I’ve included some photos below of my cup and holder in their assembled state. The foil is basically just pushed down through the wire hoop and the edges squished into gripping the wire. Be very careful to hold it up to the light to check for pinholes or cracks, the foil is delicate and tears easily.

Danza Azteca: Aguila Blanca

It’s been a while since I’ve posted a dance video, and I have to crash so I can get up for work in the morning, so I think I’ll kill two birds with one stone here. Speaking of birds (and bad puns), I’ve come across a video of the White Eagle Aztec dance (Ixtakcuauhtli in Nahuatl, Aguila Blanca in Spanish) on YouTube. This one is also courtesy of our friends Miguel Rivera and alexeix. Once again his performance is interesting not due to elaborate regalia, but due to the clear demonstration of the steps and drum rhythm, as well as his spirit and agility.

Courtesy link to alexeix’s page on YouTube for this danza video.

As to the meaning of this dance, I’m currently sketchy. I’ve seen it referenced as a warriors’ dance, which would go well with the strenuous acrobatics required and the traditional military symbolism of the eagle in traditional Aztec culture. Unfortunately, I can’t say anything conclusive one way or another at this point. I’ll have to keep looking and post an update when I find more. In the meantime, enjoy the dance!

Study Of A Contemporary Huaxtec Celebration At Postectli

I came across an interesting article by Alan R. Sandstrom on FAMSI the other night. It is a summary of his observation of a modern Huaxtec ceremony honoring one of the Tlaloque, a rain spirit named Apanchanej (literally, “Water Dweller”). This festival took place in 2001 on Postectli, a mountain in the Huasteca region of Mexico.

A bit of background — the Huaxtecs are an ancient people, neighbors of the Aztecs. Like the Aztecs, they spoke and still speak Nahuatl, making them one of the numerous Nahua peoples. To this day they still live in their traditional home, one of the more rugged and mountainous sections of Mexico. They have retained more of their indigenous culture than some of the other nations that survived the Conquest due to their remoteness and the rough terrain that inhibited colonization. This includes many pre-Conquest religious traditions, even some sacrificial practices.

To read the short article summarizing Sandstrom’s experiences at the ceremony:

If you would like to read the article in English, please go HERE.

Si desea leer el artículo en español, por favor haga clic AQUI.

Some Highlights Related To Modern Practices

This article includes discussion of several details of particular interest to those interested in learning from the living practice of traditional religion. Of special note are photographs of the altar at the shrine on Postectli, including explanation of the symbols and objects on it (photograph 12). Also, the practice of creating and honoring sacred paper effigies of the deities involved in the ceremony is explored in some depth. Paper has traditionally been a sacred material among the Nahua tribes, and paper representations of objects in worship is a very old practice indeed. Additionally, there is some detail on tobacco and drink offerings, as well as the use of music and the grueling test of endurance inherent in the extended preparation and performance of this ritual.

Contemporary Animal Sacrifice

A key part of the article’s focus is on the modern practice of animal sacrifice and blood offerings that survive among the Huaxteca today. These forms of worship have by no means been stamped out among the indigenous people of Mexico, as Sandstrom documents. (Yes, there are photographs in case you are wondering — scholarly, not sensationalistic.) Offering turkeys is something that has been done since long before the Conquest, and from what I have read they remain a popular substitute for humans in Mexico. It’s fitting if you know the Nahuatl for turkey — if I remember right, it’s pipil-pipil, which translates to something like “the little nobles” or “the children.” If I’m wrong, someone please correct me, as I don’t have my notes on the Nahuatl for this story handy at the moment. They got that name because in the myth of the Five Suns, the people of one of the earlier Suns were thought to have turned into turkeys when their age ended in a violent cataclysm, and they survive in this form today. I doubt the connection would have been lost on the Aztecs when offering the birds.

Closing Thoughts

To wrap things up, Sandstrom’s article was a lucky find and is a valuable glimpse into modern-day indigenous practice . I strongly recommend stopping by FAMSI and checking it out, as my flyby overview of it can’t possibly contain everything of interest. On one last detail, I strongly encourage you to read the footnotes on this one — a lot more valuable info is hidden in those.

Daily Priestly Offerings Of Incense

I feel like talking about the ritual of offering copal incense today. More specifically, I’d like to go into more detail about how the tlamacazqui (priests) used to offer incense each day during the height of the Aztec Empire.

Copal was burned for the Teteo almost constantly in the temples. Sahagun records in Book 2 of the Florentine Codex that the priests would offer incense nine times each day. Four of these times fell during the day, five came at night. The four during the day were when then sun first appeared, at breakfast, at noon, and when the sun was setting. The five times at night were when the sun had fully set, at bedtime, when the conch shell trumpets were blown, at midnight, and shortly before dawn.

Sadly, we don’t have exact clock times for these nine offerings. Granted, some of them, such as the offerings at sunrise and sunset, would’ve drifted with the change in light levels as the seasons passed, while those like noon and midnight would’ve been fixed. The Spanish commentary in Book 7 of the Florentine Codex does state that one of the nighttime offerings was at 10PM. My guess is that one would’ve been either the one that coincided with bedtime or the blowing of the trumpets, as it had to be one of them between sunset and midnight. I would also bet that the offering at full dark is the one where the prayer to greet the night I discussed earlier took place. This would’ve been when the Fire Drill constellation rose into the sky.

Incidentally, it seems that the midnight incense offering was the most important of the nine. Sahagun specifically points out in some places that every priest was to wake at midnight and join in the offering of incense and blood via autosacrifice. This ritual was so important that the most trustworthy of the young priests were given the duty of holding vigil at night and waking their colleagues for this ceremony. Not only that, but those who failed to wake up and join in were punished severely, frequently by additional bloodletting or by a beating. The Aztec priesthood took its duties very seriously, and lapses in function were dealt with harshly.

Furthermore, many of the huehuetlatolli (“ancient words,” or moral discourses) recorded in Book 6 of the Florentine Codex make reference to the midnight offering of incense. The especially devout people, the “friends of Tezcatlipoca,” were dutiful in their observance of this celebration. They’re described as scorning sleep to rise and worship, sighing with longing for the presence of the god and crying out to Him. Judging by these references, it appears that the midnight incense offering was also important to the general nobility as well. Not too surprising, I suppose, as most of the nobility were educated in the calmecac school, the same school that trained the young priests. In a sense, every nobleman did a stint in seminary, though not everyone went on to become professional tlamacazqui.

The incense burner typically used by the priests was ladle-shaped and made of fired clay. The long handle was hollow and filled with pebbles, so it would rattle as the priest would move about. The handle was frequently sculpted to look like a snake, an animal commonly appearing in depictions of sacred things and beings. The hot coals and copal resin would go into the spoon-like cup on the end.

Who exactly received these nine offerings of incense is currently unknown to me. At many points in the Florentine Codex, where an incense offering is described in detail, the Four Directions are noted as receiving the sweet scent and smoke, in addition to any other deities being specifically addressed. Thus, the ladle would be raised to each direction, the prayers of the priest accompanied by the rattling of the stones in the handle. Sahagun notes that some of the nighttime offerings were directed to Yohualtecuhtli, the Lord of Night, and the dawn offering went to Tonatiuh, the Sun. The midnight offering typically shows up in the context of prayers to Tezcatlipoca, at least in the huehuetlatolli I have access to.

The Anonymous Conqueror’s Narrative

Funny how things tend to come in clusters. One day I find the full text of Soustelle’s The Daily Life of the Aztecs, today I find a complete English translation of the Anonymous Conqueror’s Narrative of Some Things of New Spain and of the Great City of Temestitan, México. (In case you’re wondering, Temestitan is an old Spanish corruption of Tenochtitlan.)

This is one of the more obscure Conquest-era histories, allegedly written by one of the Conquistadores under Cortes. We’ve never definitively identified who the author was, but the book seems to be generally accepted as a genuinely early document. The book is an account of the Conquest itself and a concise overview of life in Tenochtitlan at the time, from a recently-arrived European perspective. As usual, such works have to be read carefully, with an awareness of problems of reliability, bias, and cultural misunderstandings/ignorance. With those caveats aside, however, early material like this can still be quite useful.

I have also updated the First Contact & Conquest Era History page on this site with a permanent link to this work.

Now, if you will excuse me, I’m going to go crash before I face-plant on my keyboard, as I’ve been awake for almost 24 hours straight now, 13 of which were spent at work… Just had to share this random discovery before catching some sleep.

Soustelle’s Daily Life Of The Aztecs

I was doing some digging online today, and had quite a stroke of good luck — I found a complete copy of Jacques Soustelle’s classic The Daily Life of the Aztecs online! The English edition of the entire book is available to read for free on Questia. Soustelle was a famous French anthropologist who specialized in studying the Aztecs before the Conquest, one of the bright lights in Mesoamerican studies of the mid 20th Century. His Daily Life of the Aztecs is one of his best-known works on this subject, covering a wide variety of details of Mexica life in great Tenochtitlan, ranging from architecture to agriculture, religion, economics, and the conduct of war. Though somewhat dated (written in 1962), most of the information in this book still remains quite useful, and his respectful, non-sensationalistic tone is refreshing. As it predates the rediscovery of the Templo Mayor (Huey Teocalli) in the 1970’s, it sadly doesn’t include much on that famous structure. Still, I strongly recommend giving it a read, as it remains one of the better general histories and anthropological overviews of life in Precolumbian Mexico.

Go HERE to read The Daily Life of the Aztecs in full!

Incidentally, I have now activated the Pre-Conquest History page in the History section of this blog’s static pages and placed an additional permanent link to this book there.

Aztecs At The British Museum

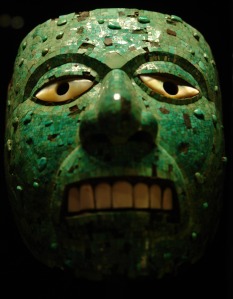

In the spirit of the aphorism “a picture is worth a thousand words,” I recommend stopping by the British Museum’s Aztec collection online. They have available 27 photographs (well, 26 if you ignore the crystal skull that’s been proven to be a hoax) of beautiful Aztec and Mixtec artifacts. Among them are statues of Quetzalcoatl, Tezcatlipoca, Mictlantecuhtli, Tlazolteotl, Tlaloc, Xochipilli, and Xipe Totec, as well as a rare mosaic ceremonial shield, a turquoise serpent pectoral, and a sacrificial knife. The images are thought-provoking and intense, as these objects speak wordlessly the vision of the Nahua peoples without Colonial censorship.

Click HERE to visit the British Museum’s Aztec Highlights.

As a bonus, I located an excellent photograph of a jade mask of Xiuhtecuhtli, God of Time and Fire, which is a part of the British Museum’s collection but is not on their website. Thank you Z-m-k for putting your fine photography skills to work on this worthy subject material and for your kindness in sharing it under the Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 2.5 License.

Identity Of The Fire Drill Constellation

Good news! My dear friend Shock answered my plea for help regarding the identity of the Fire Drill constellation that was discussed in my article on greeting the dusk. She’s studied the scholarship on Mesoamerican archaeoastronomy extensively and kindly popped in to shed some light on this issue. This is what she had to say regarding the identity of the Fire Drill:

“Anyway… About the fire drill constellation. It’s Orion’s Belt, clear as day if you look at the evidence. The Pleiades couldn’t possibly be it. It’s a seven/six star cluster within Taurus and used as a reference point for the Fire Drill in the primary source material. Taurus itself couldn’t be it for these same reasons and the fact that its other noticeable stars aren’t in a straight line. The Cygnus idea makes little to no sense considering that Sahagun clearly states in book 7 of the Florentine that the constellation is near the Pleiades. Cygnus is NOWHERE near the Pleiades in the night’s sky. In book 7, look up two parts. First, the fire drill part in Nahuatl and then Sahagun’s commentary in Spanish under Castor and Pollux. Several things are clear; the Fire Drill needs to be by Gemnini and it needs to be by Taurus. It also has to be a straight line of three bright stars. The straightness is reiterated in the Nahuatl text numerous times. And what’s right by both of these, with three bright stars? Orion’s belt. And then you have the comparative ethnography stuff from FAMSI, plus there’s more stuff similar to that which is closer to Mesoamerica.”

So, it does look like the best candidate for the Fire Drill constellation is the stars of Orion’s Belt!

Also, apparently the guy who favors the Northern Cross as the Fire Drill is a poor-quality “scholar” associated with the atrocious “mayalords.org” site, so I’d recommend ignoring him beyond the value of knowing what the crap arguments are out there.

Thanks Shock!

Incidentally, I have updated my other post with this important information for convenience and clarity.

Greeting The Dusk

“Yohualtecuhtli, the Lord of the Night, Yacahuitzli, has arrived! How will his labor go? How will the night pass and the dawn come?”

Following up on my earlier article on how the priests greeted the dawn, above is my rendition of the traditional prayer saluting the dusk. It is a modernized composite of the two variants recorded by Sahagun and Tezozomoc. (To read Dr. Seler’s translation of the Tezozomoc version, click HERE and search within the book for youaltecutli. The only hit is on page 357, containing the prayer in question.)

This prayer was traditionally offered around sundown, as a particular constellation called mamalhuaztli, the Fire Drill, rose from the east into the darkening sky. It was accompanied by the offering of incense, being another one of the nine times a day the priests would offer copal to the Teteo.

You may be wondering exactly what constellation mamalhuaztli is, as its rise was the traditional signal to perform this rite. The bad news is. . . we’re not sure. Partially because the records suck, partially because the constellations have drifted in the sky over the past millennium or so. We have enough information to know that this constellation was in the vicinity of the Pleiades, and apparently some scholars think the Fire Drill was three stars that are part of them. However, the stars in Orion’s belt are another popular theory, and at least one guy seems to consider the Northern Cross a candidate, though his credentials are suspect at best. The link above to the original language of the prayer includes some of Seler’s deductions regarding the identity of this constellation, though sadly the whole thing isn’t available. Go HERE for a very brief discussion on the Aztlan mailing list hosted by FAMSI regarding the Orion vs. Northern Cross debate if you’re curious.

Due to this uncertainty, I’d advise taking the obvious route of observing this prayer either at sunset or right at full dark. It’s not perfect, but it should be in the ballpark I’d think, and archaeoastronomy isn’t my strength. So, good enough for me, and it seems a reasonable alternative for modern practice in the face of a gap in our knowledge. However, if anyone does have a good background in this branch of astronomy and can help out, I’d be interested in hearing what you have to say about the identity of the Fire Drill constellation.

UPDATE 10/2/08:

Well, my dear friend Shock answered my plea for archaeoastronomy help on this issue! This subject is one that’s close to her heart, and she’s studied the scholarship on this area extensively. This is what she had to say regarding the identity of the Fire Drill:

“Anyway… About the fire drill constellation. It’s Orion’s Belt, clear as day if you look at the evidence. The Pleiades couldn’t possibly be it. It’s a seven/six star cluster within Taurus and used as a reference point for the Fire Drill in the primary source material. Taurus itself couldn’t be it for these same reasons and the fact that its other noticeable stars aren’t in a straight line. The Cygnus idea makes little to no sense considering that Sahagun clearly states in book 7 of the Florentine that the constellation is near the Pleiades. Cygnus is NOWHERE near the Pleiades in the night’s sky. In book 7, look up two parts. First, the fire drill part in Nahuatl and then Sahagun’s commentary in Spanish under Castor and Pollux. Several things are clear; the Fire Drill needs to be by Gemnini and it needs to be by Taurus. It also has to be a straight line of three bright stars. The straightness is reiterated in the Nahuatl text numerous times. And what’s right by both of these, with three bright stars? Orion’s belt. And then you have the comparative ethnography stuff from FAMSI, plus there’s more stuff similar to that which is closer to Mesoamerica.”

So, it does look like the best candidate for the Fire Drill constellation is the stars of Orion’s Belt!

Also, I’ve been informed that the guy who favors the Northern Cross as the Fire Drill is a third-rate “scholar” connected to the godawful “Mayalords” site, so I’d recommend ignoring him beyond the value of knowing what the crap arguments are out there.

Thanks Shock!

If you’re particularly interested in this subject, I recommend watching the Comments on this post for more.