A Few Aztec Riddles

Watching the Hobbit in theatres last weekend got me thinking about riddles. Not only are they amusing, but the figurative language and ideas contained within them can point to interesting tidbits of culture. I’ve pulled a few of my favorites from the Florentine Codex and included them below, in slightly more informal language. After each riddle and its answer I’ve added some of my own notes and interpretations of the concepts they nod to (the commentary is my own work, not that of Anderson and Dibble).

Q: What’s a small blue gourd bowl filled with popcorn?

A: It’s the sky.

Mesoamerican cosmology divides the universe into sky and heavens (topan) above, the earth’s surface like a pancake or tortilla in the middle (tlalticpac), and the underworld (mictlan) below. Though all three have their own distinct and separate characteristics, they interpenetrate to a certain degree, and this riddle hints at that in a playful manner. The gourd itself is a product of the earth and its underworld powers, doubly so as it’s a water-filled plant (and is often likened to the human head), as is popcorn. In fact, first eating corn is the moment where an infant becomes bound to the earth deities as it takes of their bounty and starts to accumulate cold, heavy “earthy-ness” within its being. It’s also the start of a debt to the earth and vegetation gods — as They feed the child, one day that child will die and return to the earth to feed Them. I covered some aspects of this idea in my Human Corn post, if you’re curious to read more.

Q: What’s the little water jar that’s both carried on the head and also knows the land of the dead?

A: The pitcher for drawing water.

The land of the dead is traditionally conceived of as a place dominated by the elements of earth and water, filled with cool, oozy dampness. Rivers, wells, springs, and caves were places where the underworld power was considered to leak through to the mortal realm. Not only did this power seep through to us, but we could sometimes cross through them to reach the underworld as well (the legendary Cincalco cave being one of the most famous of these doors). Thus, thrusting the jar down into a watering hole or a spring, breaking through the fragile watery membrane, was sending it into Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue’s world in a way.

Q: What lies on the ground but points its finger to the sky?

A: The agave plant.

The agave plant, called metl in Nahuatl and commonly referred to as a maguey in the old Spanish sources, is a plant loaded with interesting cultural associations. Its heart and sap is tapped to produce a variety of traditional and modern liquors like pulque, octli, and tequila, linking it to the earth-linked liquor gods like Nappatecuhtli, Mayahuel, and even Xipe Totec and Quetzalcoatl in their pulque god aspects. Additionally, each thick, meaty leaf is tipped with a long black spine that’s much like a natural awl. This spine was one of the piercing devices used by priests and the general public alike to perform autosacrifice and offer blood to the gods. Lastly, the beautiful greenish-blue color of the leaves of some species (like the blue agave), is the special color traditionally associated with beautiful, divine things. Take a look at a photo of the respendent quetzal’s tailfeathers — they’re just about the same color as the agave.

Q: What’s the small mirror in a house made of fir branches?

A: Our eye.

The Aztecs strongly associated mirrors with sight and understanding. Several gods, most notably Tezcatlipoca (the “Smoking Mirror”), possessed special mirrors that would allow them to see and know anything in the world by peering into them. Some of the records we have from before and during the Conquest record that some of the statues of the gods had eyes made of pyrite or obsidian mirrors, causing a worshipper standing before them to see themselves reflected in the god’s gaze. In the present day, some of the tigre (jaguar) boxers in Zitlala and Acatlan wear masks with mirrored eyes, discussed in this post and video. One last point on mirrors — in many of the huehuetlatolli (ancient word speeches), the speaker implores the gods to set their “light and mirror” before someone to guide them, symbolizing counsel, wisdom, and good example. The comparison of eyelashes to fir branches is rather interesting, as it reminds me of the common practice in many festivals of decorating altars with fresh-cut fir branches. The two elements combine to suggest a tiny shrine of enlightenment, the magic mirror nestled in its fragrant altar like a holy icon.

Q: What’s the scarlet macaw in the lead, but the raven following after?

A: The wildfire.

I included this one simply because I thought it was exceptionally creative and clever. I’m pretty sure it would stump even a master riddler like Gollum!

*****

Sahagún, Bernardino , Arthur J. O. Anderson, and Charles E. Dibble. General History of the Things of New Spain: Florentine Codex. Santa Fe, N.M: School of American Research, 1950-1982, Book VI, pp.236-239.

Aztec Art Photostream by Ilhuicamina

Happy New Year’s! Instead of fireworks, let’s ring in the new year with a superb photostream from Flickriver user Ilhuicamina. This set is of exceptional quality and covers many significant artworks excavated from the Templo Mayor and safeguarded by INAH at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Take a look!

Quiquiztli: The Conch Shell Trumpet

It’s the ending of the old baktun and the dawning of a new one, and I’d like to greet both the new era and the return of the Sun on this Winter Solstice with the blowing of conch horns!

The Aztecs named the conch shell trumpet quiquiztli, and the musicians who played them “quiquizoani.” This is the instrument that Quetzalcoatl played to defeat the devious challenge of Mictlantecuhtli, the Lord of the Dead, and reclaim the ancestral bones of humanity at the start of the Fifth Sun. I have seen some speculation that the “mighty breath” blown by the Plumed Serpent to set that newborn Sun moving in the sky was actually a tremendous blast on a conch horn. It’s the trumpet the priests played to call their colleagues to offer blood four (or five) times a night in the ceremony of tlatlapitzaliztli, and also during the offering of incense, according to Sahagun in the Florentine Codex . Tecciztecatl, the male Moon God, is sometimes depicted emerging from the mouth of a quiquiztli. The sound of the instrument itself was considered by the Aztecs to be the musical analog to the roar of the jaguar. Like the twisting spiral within the shell, the associations are nearly endless, doubling back on each other in folds of life, death, night, dawn, and breath.

The quiquiztli appeared in two offerings at the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan (offering #88). One shell was found on Tlaloc the Rain Lord’s side (not at all surprising, given the overwhelming watery connotations of the instrument). A second one was found on Huitzilopochtli’s side of the manmade replica of Coatepetl. If you would like to actually hear one of these very trumpets being played, you can click HERE to visit the International Study Group on Music Archaeology’s page for these trumpets. You can directly download the MP3 recording by clicking HERE.

I also found a beautiful photograph of an Aztec or Mixtec conch trumpet (covered in intricate carvings) currently in the holdings of the Museum of Fine Arts here in Boston. If you’d like to view the photo and see their notes on the artifact, please click HERE. If you’d rather jump right to the full-size, more detailed image, click HERE instead.

Want to learn more about the trumpet and its uses in Mesoamerican cultures past and present? Head on over to Mixcoacalli and read Arnd Adje Both’s excellent 2004 journal article called “Shell Trumpets in Mesoamerica: Music-Archaeological Evidence and Living Tradition” (downloadable full text PDF). It gives a valuable introduction to the instrument in Teotihuacan, Aztec, and Mayan societies and includes numerous interesting photos and line sketches as a bonus. I couldn’t find a direct link to the article on his site, but I did find it on his server via Google. As a courtesy, the link to his homepage is here. There is some other interesting material relating to the study of ancient Mesoamerican music on there, so I recommend poking around.

What about South American cultures? I’m a step ahead of you — why not go here to read an interesting article on Wired about a cache of 3,000 year old pre-Incan shell trumpets found in Chavin, Peru? Includes recordings and photos.

Finally, if you’re curious for an idea of how the Aztecs and Maya actually played the quiquiztli, including how they changed the tone of the instrument without any finger-holes or other devices, you can view a demonstration by ethnomusicologist John Burkhalter below. If you noticed that the trumpeter in the codex image I embedded earlier has his hand slipped into the shell, you’ll get to see what that actually does when the horn is played in the video.

Aztecs At The British Museum

In the spirit of the aphorism “a picture is worth a thousand words,” I recommend stopping by the British Museum’s Aztec collection online. They have available 27 photographs (well, 26 if you ignore the crystal skull that’s been proven to be a hoax) of beautiful Aztec and Mixtec artifacts. Among them are statues of Quetzalcoatl, Tezcatlipoca, Mictlantecuhtli, Tlazolteotl, Tlaloc, Xochipilli, and Xipe Totec, as well as a rare mosaic ceremonial shield, a turquoise serpent pectoral, and a sacrificial knife. The images are thought-provoking and intense, as these objects speak wordlessly the vision of the Nahua peoples without Colonial censorship.

Click HERE to visit the British Museum’s Aztec Highlights.

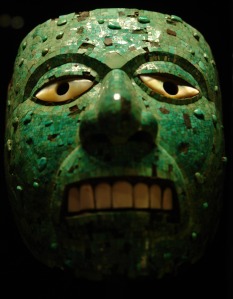

As a bonus, I located an excellent photograph of a jade mask of Xiuhtecuhtli, God of Time and Fire, which is a part of the British Museum’s collection but is not on their website. Thank you Z-m-k for putting your fine photography skills to work on this worthy subject material and for your kindness in sharing it under the Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 2.5 License.

Quetzalcoatl’s Descent To Mictlan, the Land of the Dead

A change of pace for today, because I’m in a storytelling mood and I even found a kickass danza video to go with it. Today I’ll tell the legend of how Quetzalcoatl brought humanity back to life by stealing the precious bones from the Lord of the Land of the Dead, Mictlantecuhtli.

This version of the “Quetzalcoatl goes to Mictlan” tale is a composite of the several different variants of the myth that exist, and the wording of it is completely my own. I fleshed it out a bit in order to try to restore some of the richness and “naturalness” that gets lost when you try to take an oral tradition that was typically performed with song and dance and try to move it to the written page, especially if you have to translate it to boot.

As a bonus, I found a danza video showing a beautiful dance rendition of the story! I’m going to put that in its own post so the formatting doesn’t get all awkward. So, let’s get started!

Quetzalcoatl’s Descent To Mictlan

As told by Cehualli

It was the beginning of the Fifth Sun. Newborn Tonatiuh shone His light over the earth below. His rays revealed the beauty of the recreated land and sea, yet the gods were unhappy with what They saw. Why? The world was empty of life.

The gods gathered to share Their sorrow at the absence of Their creatures. “We’ve brought the earth and sky back together and made them whole again, but what good is it all without anyone to live there? Who will worship Us? We can’t let things go on like this!”

But the humans were all dead, killed when the Fourth Sun fell in a torrent of rain. And the dead were far away, hidden deep in Mictlan, the Land of the Dead. Mictlantecuhtli and Mictlancihuatl, the Lord and Lady of that cold, dark, silent realm, now kept their bones as treasures. Without the bones, there could be no more humans.

The Teteo continued, “We must give life back to the humans, our faithful servants who We first created long ago. But We need their bones to recreate them, and they are lost in Mictlan. Someone must go down to the Land of the Dead and persuade Mictlantecuhtli and Mictlancihuatl to give them back to Us. But who among Us is best suited for this dangerous quest?”

After a few moments of deliberation, Quetzalcoatl and His twin, Xolotl, nodded to each other and stepped forward. Xolotl, the god with the serious face of a great hound, said, “I am Xolotl, the Evening Star. Every night, I lead the Sun down to Mictlan to die. I know the way to the Land of the Dead and will guide us there.”

Quetzalcoatl, His wise old face wreathed with a beard of brilliant feathers, said, “I am Quetzalcoatl, the Morning Star. Every morning, I lead the Sun back out of Mictlan to be reborn with the dawn. I know the way out of the Land of the Dead and will guide us back home to sweet Tamoanchan.”

The rest of the gods heard Their brave words and thought the plan wise. Tezcatlipoca said, “Though We may fight and compete for glory, Brother Quetzalcoatl, I too want to see the humans brought back from Mictlan. May You succeed in bringing back the bones.”

With that said, Xolotl and Quetzalcoatl set out from Tamoanchan, descending towards the Land of the Dead. The other gods watched Them go with great concern, for They knew that Mictlantecuhtli was a proud and cunning king who wouldn’t give up the bones willingly. They gathered around Tezcatlipoca’s smoking mirror, a device of wonderful power through which the god could see everything, to watch the progress of the twins and wait.

Xolotl led the way down to Mictlan and through the nine layers of the Realm of Death. They retraced the path that the Sun took every night down into the depths of the underworld, all the way to the palace of the Lord of the Dead. “We must be careful,” Quetzalcoatl said. “I know Mictlantecuhtli will not be pleased by Our request. He is a wily god and may try to trap Us.” Xolotl agreed, and They cautiously proceeded to the throne of the Lord and Lady of the Dead.

Mictlantecuhtli was waiting for Them. “Welcome to My kingdom, gods from the bright realm of Tamoanchan. What brings You so far from your home?” Scattered around the royal chamber were heaps of the bones of the humans, piled up like treasure.

Quetzalcoatl spoke respectfully, one god to another. “We have come for the precious bones of the humans. We have need of them in Tamoanchan.”

Mictlantecuhtli eyed the two gods. “And why do You need my lovely bones? It must be very important if You came all the way to the Land of the Dead.” Already He seemed to be planning something.

Quetzalcoatl replied, “The Fifth Sun has dawned, and it’s time for humans to walk the earth and bask in His rays again. We need those bones so we may bring them back to life.”

Mictlantecuhtli frowned, and the chill in the air deepened. “And how do I benefit from this? No, I don’t think I’ll give up my splendid bones. If I give them to You, I’ll never get them back and I’ll be poorer for it. No, You can’t have My bones.”

Quetzalcoatl had anticipated this. “Oh, no! You misunderstand Me. We don’t intend to keep the bones, We just want to borrow them. The humans would be mortal, and would eventually return to You, just like how everything else is born and eventually dies, even the Sun itself. Only we Teteo live forever. You wouldn’t really lose anything in the end, and in the meantime, Your fame would grow.”

Mictlancihuatl looked pleased by these words. Mictlantecuhtli considered them, then spoke. “Hmmm. An interesting idea. All right. You can have the bones…” Xolotl began to move towards the bones. “IF” continued Mictlantecuhtli. Xolotl froze. “IF You can play My conch-shell trumpet and circle My kingdom four times in honor of Me.”

“Of course,” said Quetzalcoatl. Mictlantecuhtli gave Them His trumpet and watched Them leave His throne room. He smiled, satisfied that He wouldn’t have to give up those bones after all…

Xolotl looked at the trumpet in dismay. The conch shell had no holes and couldn’t make a sound. “He’s trying to trick Us!”

“I’ve got a plan,” said Quetzalcoatl. And He called the worms and other gnawing insects, and ordered them to chew holes into the conch shell. Then He took the shell and held it up, and summoned the bees to climb inside through the holes and buzz loudly. The sound echoed through the shadowy realm like a trumpet blast.

Mictlantecuhtli hid a scowl when Quetzalcoatl and Xolotl marched proudly back into the throne room. “We’ve done what You asked, Lord of the Dead. Now, give Us the bones as You agreed!”

“Very well then,” said Mictlantecuhtli, calm again. “You can have them for now. But the humans will not be immortal. They must die again someday and return to me, just as You had said earlier.” The Morning and Evening Star agreed, gathered up the bones, and left.

Mictlancihuatl looked horrified. “Our treasure! We can’t let Them carry it off!”

“Of course We won’t. I may have said They could have the bones. I never said They could leave My kingdom with them.” And then He ordered some of his servants to dig a pit along the path that the two gods must take to escape, and others to chase after Them.

Quetzalcoatl and Xolotl saw the army of the Lord and Lady of the Dead in hot pursuit, and ran as fast as They could, up towards the way out of Mictlan. Looking back at the mob chasing them, They didn’t see the pit ahead.

Suddenly, a flock of quail burst out of hiding, surrounding the two gods and startling Them. Quetzalcoatl slipped and fell into the pit, then Xolotl heard a sickening crunch of breaking bone. “What happened?” cried Xolotl, running over to help.

Quetzalcoatl was looking in horror at the bones. They had shattered into pieces, and some of the quail were gnawing on them. He chased away the quail and sifted through the bones, weeping. “They’re ruined! Now what will We do?”

Xolotl said, “Maybe they will still work, and We can still make this turn out for the best. It’s the only thing We can do now.” And He helped Quetzalcoatl gather up the broken bones in a bundle and escape with them.

They got back to Tamoanchan and showed the rest of the Teteo the ruined bones. Cihuacoatl looked at the pieces thoughtfully, then smiled. “We can still bring the humans back to life.” Then She took the shattered bones and ground them up like corn in a clay bowl, turning them into a fine powder. Then Quetzalcoatl bled His penis into the bowl, and the rest of the gods also gave blood. The blood mixed with the ground bones, and immediately living humans formed.

The gods rejoiced. “We’ve succeeded, the macehuales (literally, “those gained by divine sacrifice”) are born! The earth will be filled with humans once again. They will worship Us, and We will be their gods.”

And that is the story of how Quetzalcoatl went to Mictlan and brought back the precious bones so that humans could be reborn into the age of the Fifth Sun.