Pestilence and Headcolds: Encountering Illness in Colonial Mexico

I’ve noticed a boom in people dropping by my post about the Codex Badianus, an Aztec book of medicine. Sadly, I’ve never found a full-text copy of that one online as all the translations so far seem to be still under copyright. However, I did find an entire academic exploration of sickness and medicine in Mexico during the colonial period, Pestilence and Headcolds: Encountering Illness in Colonial Mexico! Written in 2008 by Sherry Fields, it covers how the colonized peoples of Mexico understood and dealt with illness and health, including viewpoints spanning from persistent pre-Conquest traditions to Colonial syncretisms to the new European concepts. Of particular interest are sections drawn from native-generated primary sources and contemporary colonial medical records. The author’s kindly made the whole text available to read online for free. To check it out, look below.

Go HERE to read Pestilence and Headcolds: Encountering Illness in Colonial Mexico.

A Few Aztec Riddles

Watching the Hobbit in theatres last weekend got me thinking about riddles. Not only are they amusing, but the figurative language and ideas contained within them can point to interesting tidbits of culture. I’ve pulled a few of my favorites from the Florentine Codex and included them below, in slightly more informal language. After each riddle and its answer I’ve added some of my own notes and interpretations of the concepts they nod to (the commentary is my own work, not that of Anderson and Dibble).

Q: What’s a small blue gourd bowl filled with popcorn?

A: It’s the sky.

Mesoamerican cosmology divides the universe into sky and heavens (topan) above, the earth’s surface like a pancake or tortilla in the middle (tlalticpac), and the underworld (mictlan) below. Though all three have their own distinct and separate characteristics, they interpenetrate to a certain degree, and this riddle hints at that in a playful manner. The gourd itself is a product of the earth and its underworld powers, doubly so as it’s a water-filled plant (and is often likened to the human head), as is popcorn. In fact, first eating corn is the moment where an infant becomes bound to the earth deities as it takes of their bounty and starts to accumulate cold, heavy “earthy-ness” within its being. It’s also the start of a debt to the earth and vegetation gods — as They feed the child, one day that child will die and return to the earth to feed Them. I covered some aspects of this idea in my Human Corn post, if you’re curious to read more.

Q: What’s the little water jar that’s both carried on the head and also knows the land of the dead?

A: The pitcher for drawing water.

The land of the dead is traditionally conceived of as a place dominated by the elements of earth and water, filled with cool, oozy dampness. Rivers, wells, springs, and caves were places where the underworld power was considered to leak through to the mortal realm. Not only did this power seep through to us, but we could sometimes cross through them to reach the underworld as well (the legendary Cincalco cave being one of the most famous of these doors). Thus, thrusting the jar down into a watering hole or a spring, breaking through the fragile watery membrane, was sending it into Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue’s world in a way.

Q: What lies on the ground but points its finger to the sky?

A: The agave plant.

The agave plant, called metl in Nahuatl and commonly referred to as a maguey in the old Spanish sources, is a plant loaded with interesting cultural associations. Its heart and sap is tapped to produce a variety of traditional and modern liquors like pulque, octli, and tequila, linking it to the earth-linked liquor gods like Nappatecuhtli, Mayahuel, and even Xipe Totec and Quetzalcoatl in their pulque god aspects. Additionally, each thick, meaty leaf is tipped with a long black spine that’s much like a natural awl. This spine was one of the piercing devices used by priests and the general public alike to perform autosacrifice and offer blood to the gods. Lastly, the beautiful greenish-blue color of the leaves of some species (like the blue agave), is the special color traditionally associated with beautiful, divine things. Take a look at a photo of the respendent quetzal’s tailfeathers — they’re just about the same color as the agave.

Q: What’s the small mirror in a house made of fir branches?

A: Our eye.

The Aztecs strongly associated mirrors with sight and understanding. Several gods, most notably Tezcatlipoca (the “Smoking Mirror”), possessed special mirrors that would allow them to see and know anything in the world by peering into them. Some of the records we have from before and during the Conquest record that some of the statues of the gods had eyes made of pyrite or obsidian mirrors, causing a worshipper standing before them to see themselves reflected in the god’s gaze. In the present day, some of the tigre (jaguar) boxers in Zitlala and Acatlan wear masks with mirrored eyes, discussed in this post and video. One last point on mirrors — in many of the huehuetlatolli (ancient word speeches), the speaker implores the gods to set their “light and mirror” before someone to guide them, symbolizing counsel, wisdom, and good example. The comparison of eyelashes to fir branches is rather interesting, as it reminds me of the common practice in many festivals of decorating altars with fresh-cut fir branches. The two elements combine to suggest a tiny shrine of enlightenment, the magic mirror nestled in its fragrant altar like a holy icon.

Q: What’s the scarlet macaw in the lead, but the raven following after?

A: The wildfire.

I included this one simply because I thought it was exceptionally creative and clever. I’m pretty sure it would stump even a master riddler like Gollum!

*****

Sahagún, Bernardino , Arthur J. O. Anderson, and Charles E. Dibble. General History of the Things of New Spain: Florentine Codex. Santa Fe, N.M: School of American Research, 1950-1982, Book VI, pp.236-239.

Aztec Art Photostream by Ilhuicamina

Happy New Year’s! Instead of fireworks, let’s ring in the new year with a superb photostream from Flickriver user Ilhuicamina. This set is of exceptional quality and covers many significant artworks excavated from the Templo Mayor and safeguarded by INAH at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Take a look!

Xultún And The Baktun

In honor of the approaching end of the 13th baktun on December 21, per the famous Mayan calendar, I’d like to write about a piece of ironclad historical evidence contradicting the “Mayan doomsday” nonsense. That particular piece of evidence lies in the ruins of Xultun.

Xultun was once a flourishing Mayan metropolis, and its importance continues to the present day as the site of a series of murals of great significance to clearing up an archaic misunderstanding of the great calendar. More specifically, painted on the walls in a house that appears to have been a workshop for scribes and astronomers, is a series of complex astronomical tables extending well past the end of 2012. In other words, the Mayan astronomers of the ninth century C.E. most certainly didn’t think the world would end when the thirteenth baktun did, but instead carried on with their work charting planetary and stellar activities well beyond the supposed end of the world. “So much for the supposed end of the world,” quips William Saturno, one of the present-day (re) discoverers of these scientific calculations.

Another of Saturno’s comments sums up the contrast between Western pop culture’s misconceptions and Mayan thought nicely, in my opinion — “We keep looking for endings… the Maya were looking for a guarantee that nothing would change. It’s an entirely different mindset.” (National Geographic, 5/10/2012)

After the above excerpts, you might be interested in getting a look at Xultun and these murals for yourself. If so, you’re in luck!

If you click HERE, you can view National Geographic’s “Giga Pan” high resolution photographs of some of the murals.

If you’d like to explore the beautiful stone stelae (carvings) that dot the city, you can click HERE to visit the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard’s website cataloguing a bit of the site’s history, its carvings, and their locations around the town. (The diagrams of the carvings are in the list on the lefthand side of the page.)

Finally, National Geographic has also prepared a short video on the discoveries at Xultun for your viewing pleasure, which you can view HERE if you have trouble viewing the embedded version below.

Conquistador Helm In Salem, MA Part 2

A quick post today to follow up on my last one. I was digging through a disc of photos my father took while we were visiting Salem, and it turns out he also snagged a shot of the conquistador’s helmet. He had a proper DSLR camera with him and was able to get a larger, higher resolution photo of the helm, so I’m posting it too so you can get a more detailed look. As always, click to view the image in its full size.

Conquistador Helm In Salem, MA

Earlier this month I visited the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, MA and spotted a surprising object in their collection. Amidst the lovely array of East Asian artwork (better than the MFA’s holdings in Boston proper, in my opinion), nautical paintings and artifacts, and other marvels, sitting unobtrusively on a shelf in their gallery devoted to curios collected by local sailors from around the world, sits a conquistador’s helmet. I snapped a couple of photos to share with you all (please excuse the quality, I wasn’t planning on doing any photography and flashes were forbidden in the museum to boot). Click to view the photos full size.

First, a shot of the whole helmet on its shelf.

Next, a close-up of the antique paper label pasted on the helm by a museum curator (presumably) a long time ago. Judging by the paper, ink, and handwriting style, I’m guessing it was attached to the artifact sometime in the 19th century. The label reads “An Ancient Spanish H[elmet] found in Mexico, and probably [worn?] by some of the followers of Cortez.”

Aztecs In The Werner Forman Archive

Tonight I’ve decided to bring your attention to a major collection of photographs of Aztec and other Mesoamerican art, crafts, and architecture. It’s housed at the Werner Forman Archive in the United Kingdom. It’s a treasure trove of wonderful pictures of literally thousands of different objects and places around the world, including pictures relating to the Aztecs, Maya, Teotihuacanos, and other peoples of Central America.

Click HERE to enter the Archive and begin browsing or searching.

You can browse their Precolumbian section for photos covering both North and South American peoples, or you can try searching for Aztec, Maya, or more specific keywords. To give you a hint at how much there is to explore, the full Precolumbian section has 763 photos available online!

As they don’t appear to look kindly on people rehosting their images, and hotlinking is rude, I’ll just drop a few direct links here to some particularly interesting photos to get you started…

Click here to see a sculpture of Tlaloc, Lord of Storms and Tlalocan, in His Earth-lord guise.

Want to see a pectoral device in the shape of a chimalli (shield)?

How about Quetzalcoatl’s signature necklace, the wind jewel?

Two Aztec Censer Photos

While browsing links and foraging for data, I came across an excellent pair of photos on Flickr that tie in nicely with yesterday’s post on pre-Conquest Aztec censers. Both photographs were taken by Lin Mei in 2006 at the Museo del Templo Mayor (Museum of the Grand Temple) and adjacent excavation site of the Huey Teocalli itself in Mexico City. They are hosted on Rightstream’s Flickr photostream as a part of his Templo Mayor set of images. I recommend taking a look at the full set in addition to the two I’m highlighting here, as the photos are very good quality and provide a good look at many of the fascinating examples of Mexica art and architecture uncovered by the Templo Mayor archaeology team. My thanks to Leo and Lin Mei for generously allowing their work to be shared under a Creative Commons 2.0 license.

The first photo is a beautiful example of a ladle-type censer, intended to be carried in the hand and used to incense places, people, sacred images, etc. It’s the design Walter Hough described as being derived from a basic tripod incense burner design, where one leg is elongated into a handle, producing a ladle form.

Image 055 in Rightstream’s Flickr photostream, photograph taken by Lin Mei in 2006

Used under a Creative Commons 2.0 License

The second image is a picture of the large, stationary stone brazier Hough described as being used for burning incense, offerings, ritual implements and paraphernalia, and as vessels for sacred temple fires that were never allowed to go out. The popochcomitl in the photo below is beautifully preserved, and a great amount of sharp, clear detail is apparent. Look closely at the narrow waist of the hourglass shape, and you’ll see the belt-like knotted bow I discussed yesterday. It’s a much better example than the grainy turn of the century photograph available in the linked article. You’ll also notice a beautiful monolithic serpent head nestled between the two braziers. The alternating brazier – serpent – brazier pattern continues over large sections of the stepped pyramid. It’s a logical motif when one remembers that the Grand Temple, at least on the southern side where Huitzilopochtli’s sanctuary was, is a man-made replica of the Coatepetl (Snake Mountain) where Huitzilopochtli was born and defeated the jealous Southern Stars. If you’d like to read that story, you can click HERE for my retelling of that exciting narrative.

Image 001 in Rightstream’s Flickr photostream, photograph taken by Lin Mei in 2006

Tigre Boxing In Acatlan: Jaguar & Tlaloc Masks

Up today is another video about the Mexican Tigre combat phenomenon I discussed a few weeks ago. This one shows a style of fighting practiced in Acatlan. Instead of rope whip-clubs as in Zitlala, these competitors duel with their fists.

Courtesy link to ArchaeologyTV’s page on YouTube for this Tigre combat video.

A particularly interesting feature of this video is the variety of masks. Not only do you see the jaguar-style masks, but you’ll also see masks with goggle eyes. Goggle eyes are, of course, one of the signature visual characteristics of Tlaloc, the very Teotl this pre-Columbian tradition was originally dedicated to. (And still is in many places, beneath the surface layer of Christian symbols.) If you look closely, you might notice that some of the goggle eyes are mirrored. The researchers behind ArchaeologyTV interviewed one of the combatants, who said that the significance of the mirrors is that you see your own face in the eyes of your opponent, linking the two fighters as they duel.

This idea of a solemn connection between two parties in sacrificial bloodshed was of major importance in many of the pre-Conquest religious practices of the Aztecs. It can be seen most clearly in the gladiatorial sacrifice for Xipe Totec during Tlacaxipehualiztli. During this festival, the victorious warrior would refer to the man he captured in battle as his beloved son, and the captive would refer to the victor as his beloved father. The victim would be leashed to a round stone that formed something of an arena, and given a maquahuitl that had the blades replaced with feathers, while his four opponents were fully-armed. As the captor watched the courageous victim fight to the death in a battle he couldn’t win, he knew that next time, he might be the one giving his life on the stone to sustain the cosmos.

Tigre Rope Fighting In Zitlala

Following up on last week’s post discussing the survival of Precolumbian gladiatorial combat in honor of Tlaloc in Mexico, I’ve got a video today that actually shows part of a Tigre whip match at Zitlala. Now that this activity has come to my attention, it’s something I’ll be watching for videos of in addition to Danza Azteca. It’s interesting getting to actually see the story behind the jaguar mask and contemplate the deeper meaning behind the fighting.

Courtesy link to ArchaeologyTV’s page on YouTube for this Tigre combat video.

In case you’re wondering, the special rope club used by Tigre fighters in Zitlala are called cuertas. The modern cuerta itself is actually a “friendlier” version of heavier rawhide and stone clubs used previously, which in turn were descended from stone and shell clubs used when the battles may well have been lethal. For obvious reasons, the present-day trend has been away from fatal contests, though the underlying meaning of giving of oneself to Tlaloc for a plentiful harvest endures today among those who remember.

Tlaloc In Zitlala

Came across an interesting photograph recently that’s quite interesting, as it shows an aspect of a Pre-Columbian ceremony still surviving today in Zitlala, Mexico.

Tigre Fighter With Whip & Jaguar Mask. Copyright 2008 by the Associated Press/Eduardo Verdugo. Used without permission.

Link to original photograph source.

Original Caption:

“A man dressed as a tiger carries a small whip made from rope in Zitlala, Guerrero state, Mexico, Monday, May 5, 2008. Every year, inhabitants of this town participate in a violent ceremony to ask for a good harvest and plenty of rain, at the end of the ceremony men battle each other with their whips while wearing tiger masks and costumess. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)” [Cehualli’s note — “tiger” is a common mistranslation of “tigre,” when the context makes it apparent a jaguar or other large cat is meant.]

Now…there’s a lot more going on here that the photographer doesn’t get into in his note. Specifically, that this is a modern survival of traditional indigenous religious practices.

Why do I think this? Let me explain.

There’s a certain ancient god of rain in Mesoamerica who has traditionally been associated with jaguars… and that’s Tlaloc. In the codices, if you look carefully you can see that He’s always depicted with long, fearsome jaguar fangs. The growl of the jaguar resembles the rolling of distant thunder, and the dangerous power of such an apex predator fits the moody, explosive-tempered Storm Lord quite nicely. The jaguar as a symbol of Tlaloc is a very ancient tradition that appears across the whole of Central America, whether the god is being called Tlaloc, Cucijo, Dzahui, or Chaac.

The whip-club is another hint. Flogging has been done as part of rain ceremonies for Tlaloc for centuries (I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s symbolic of lightning). Additionally, though the photographer didn’t mention this, one knows what happens when people strike each other hard with whips like the one the man in the photo is shown carrying — you bleed. A lot.

In Prehispanic Mexico, one of the important rituals for Xipe Totec, the Flayed Lord, god of spring and new growth, is called “striping.” Striping involved shooting the sacrificial victim with arrows for the purpose of causing his blood to drip and splash on the dry earth below, symbolizing rain that would bring a good harvest. Similar rituals specifically devoted to Tlaloc were also done, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the gladiatorial combat done for Xipe Totec had the same basic idea in mind, sprinkling blood over the ground done to call the rain.

The next part is due to my good friend Shock and her impressive knack for research. While we were discussing this photo, Shock directed me to an excellent article about this phenomenon known as “Tigre Boxing” that still exists all throughout Mexico today. It even discusses this specific form of battling with whips in Zitlala that this photograph is of. I highly recommend checking it out, as it’s loaded with more information about the surviving practice of gladiatorial combat for rain, complete with many excellent photos of the jaguar masks, sculptures, and even videos of the combat!

Aztecs At The British Museum

In the spirit of the aphorism “a picture is worth a thousand words,” I recommend stopping by the British Museum’s Aztec collection online. They have available 27 photographs (well, 26 if you ignore the crystal skull that’s been proven to be a hoax) of beautiful Aztec and Mixtec artifacts. Among them are statues of Quetzalcoatl, Tezcatlipoca, Mictlantecuhtli, Tlazolteotl, Tlaloc, Xochipilli, and Xipe Totec, as well as a rare mosaic ceremonial shield, a turquoise serpent pectoral, and a sacrificial knife. The images are thought-provoking and intense, as these objects speak wordlessly the vision of the Nahua peoples without Colonial censorship.

Click HERE to visit the British Museum’s Aztec Highlights.

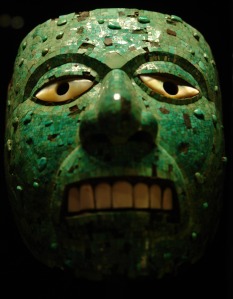

As a bonus, I located an excellent photograph of a jade mask of Xiuhtecuhtli, God of Time and Fire, which is a part of the British Museum’s collection but is not on their website. Thank you Z-m-k for putting your fine photography skills to work on this worthy subject material and for your kindness in sharing it under the Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 2.5 License.

Images Of Autosacrifice

I knew I’d come across images of autosacrifice in the codices before! I’ve included two below so you can see how the Aztecs depicted themselves performing ritual bloodletting to benefit the gods.

Tongue Piercing

Page 9, Recto, of the Codex Telleriano-Remensis

The image above is taken from the Codex Telleriano-Remensis, a Post-Conquest religious text painted by Aztec artists in a style that is a hybrid of Mexican and European art. The worshipper is piercing his tongue and letting the blood flow as a gift to the Teteo. The tool in his hand looks like a pointed stick, rather than a thorn, bone perforator, or obsidian shard, so I believe this painting may be depicting the practice of “drawing straws through the flesh” I mentioned in my article on traditional forms of autosacrifice. If anyone’s got more information on this particular image, I’m all ears.

Numerous Piercings

Page 79, Recto, of the Codex Magliabecchiano

This second image comes from the Codex Magliabecchiano, another Post-Conquest codex drawn in a European-influenced style and speaking of religious subjects. This picture shows a group of worshippers doing many different forms of autosacrifice. One is piercing his tongue, while the other is piercing his ear. The green coloration of the objects they’re using to bloodlet makes me wonder if they’re either exaggerated maguey thorns or perforators made of jade. Given the traditional use of maguey thorns for this purpose and the association of jade with blood (as both are exceedingly precious), I could go either way. Again, if anyone knows more, please drop me a comment.

Additionally, we can see that these two worshippers have already completed more rounds of bloodletting than the forms they’re in the middle of in the picture. See the blood on their arms and legs? They’ve either been piercing in those places, or have nicked themselves with shards of obsidian or flint. Incidentally, the bag-like objects slung over their arms are traditional incense pouches. They were often made with paper and beautifully decorated, and would be filled with copal resin to be burned for the gods.