That Is Not Dead Which Can Eternal Lie

In honor of the springtime finally rolling around after this seemingly-endless winter, I’d like to introduce you to a mysterious creature which the Aztecs said dies and rises with the seasons.

“In the winter, it hibernates. It inserts its bill in a tree; [hanging] there it shrinks, shrivels, molts. And when [the tree] rejuvenates, when the sun warms, when the tree sprouts, when it leafs out, at this time [it] also grows feathers once again. And when it thunders for rain, at that time it awakens, moves, comes to life.”

What is this mysterious creature that defies death?

It’s the hummingbird (huitzitzili in Nahuatl).

Incidentally, remember that the hummingbird is Huitzilopochtli’s symbol, and note that many hummingbirds, including several species in Mexico, have the brilliant blue-green color of divinity for their plumage, just like another sacred bird, the resplendent quetzal. These feathers, believed to have been shed like dead leaves in the fall, are linked to fresh, living plants by Sahagun’s informant, called into existence after the warmth of the sun, power of the sky gods, works in tandem with the watery might of Tlaloc and the other earth and vegetation gods, spiraling together to burst forth in life and movement. Thus, a bird that’s possibly the perfect representation of the sky with its ability to hover and move at will in the air, shows its other face as a facet of the earth/water/plant divinity complex, a deity web that also extends into the realm of the dead. Thus, this tiny little winged jewel is a microcosm of the vast world around it and the deities interwoven in the system.

“Canto del Colibri,” courtesy of jjeess11

*****

Sahagún, Bernardino , Arthur J. O. Anderson, and Charles E. Dibble. General History of the Things of New Spain: Florentine Codex. Santa Fe, N.M: School of American Research, 1950-1982, Book XI, pp.24.

Alarcón: Prayers For Protection From Evil While Sleeping

Among the populace of the Aztec empire, the line between religion and magic often blurred in day to day life. While the priestly class held a great amount of power in mediating between the people and the gods, and by extension had a powerful influence on directing orthodoxy, folk practices flourished within the family household. One of these was the practice of offering prayers and desirable substances (often copal incense, tobacco, and sometimes blood) to the lesser spiritual beings inhabiting everything from the trees to the crops to the tools by which people lived. While these animistic entities were less grand than the mighty cosmic lords like Huitzilopochtli and Quetzalcoatl, with their broad power over the universe and the state, these local spirits had their own gifts. This influence carried extra weight for the humble individual due to its intimate proximity — while Tezcatlipoca’s wrath could lay waste to the entire kingdom, the fury of a small farmer’s sole cornfield could prove just as deadly for that individual as his livelihood dried up.

In this post, I’ll share with you a set of three of these short folk prayer-spells, collected by the inquisitor Hernando Ruiz de Alarcón in his “Treatise on Heathen Superstitions” in the early 17th century. These incantations were intended to guard a sleeper against evildoers invading his or her home in the night, and to express gratitude in the morning for a safe rest. Note that the supplicant in these prayers is actually praying to the spirits of their bed and their pillow, rather than a more familiar high god like Tlaloc. Incantations are quoted from the excellent English translation of Alarcón by J. Richard Andrews and Ross Hassig. Incidentally, if you can read Spanish, I found a full text copy of the Paso y Tronsco fascimile online at the Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, viewable by clicking HERE. Commentary about each prayer is my own material.

Let it be soon, O my jaguar mat, you who lie opening your mouth toward the four directions. You are very thirsty and also hungry. And already the villain who makes fun of people, the one who is a madman, is coming. What is it that he will do to me? Am I not a pauper? I am a worthless person. Do I not go around suffering poverty in the world?

The supplicant here calls upon his bed (“jaguar mat”), a mat made of reeds and palm fronds to protect him from the nocturnal sorcerer, the nahual. This particular flavor of witch was greatly feared throughout the region due to his ability to control minds, paralyze, and shapeshift. He was believed to often indulge in robbery like a cat burglar, breaking into homes in the dead of night to bewitch and rob his prey. Sometimes, he would violate and kill his victims. Interestingly, Quetzalcoatl was noted by Sahagún in the Florentine Codex to be the patron of this supernatural lawbreaker.

The structure of this prayer is double-layered — the supplicant begins with calling on the spirit of his bed to protect him, but then shifts to make a declaration of his extreme poverty and worthlessness as a robbery target. Perhaps he had in mind a subtle defense here — rather than asking the spirit to try to destroy or disempower the witch, which might be unlikely to work as they were considered to be quite strong, he’s asking it to trick the burglar by convincing him that there’s nothing of value in this house, better go somewhere else.

The bed itself is described in an interesting way. It reaches out towards the four directions, thus anchoring it very firmly in physical space, but also possibly linking it to the greater spiritual ecosystem, as a common verbal formula of invoking the whole community of the divine is to call to all the directions and present them with offerings. It also reminds me of the surface of the earth (tlalticpac) which similarly fans out as a flat plane towards the cardinal directions, making the bed a tiny replica of the earthly world. The reference to gaping mouths, hunger, and thirst acknowledges that the spirit of the bed has its own needs and implies that the speaker will attend to them. In the Aztec world, nothing’s free, and a favor requested is a favor that will have to be paid for. Alarcón doesn’t note what offering is given to the mat here, but in other invocations of household objects recorded in the book, tobacco and copal smoke come up repeatedly.

Let it be soon, O my jaguar seat, O you who are wide-mouthed towards the four directions. Already you are very thirsty and also hungry.

This prayer is the companion of the one discussed above, except directed to the sleeper’s pillow (the “jaguar seat”). Incidentally, you might be wondering why these two objects are named “jaguar.” Andrews and Hassig speculate in their commentary that it may have been inspired by the mottled appearance of the reeds making up the bedding. I think it may be a way of acknowledging that these simple, seemingly-mundane objects house a deeper, supernatural power. The jaguar is a creature of the earth, of the night, and sorcery in Mesoamerican thinking, and in particular is a symbol of Tezcatlipoca. It doesn’t seem like a coincidence to me that a nocturnal symbol is linked to things so intimately tied to sleep and being interacted with in the context of their magical power. The adjective “jaguar” also appears elsewhere in Aztec furniture as the “jaguar seat” of the kings and nobles, which is often used as a symbol of lordly authority. The gods themselves are sometimes drawn sitting on these jaguar thrones, including in the Codex Borbonicus (click to view). Once again, another possible link to ideas of supernatural power and rulership — authority invoked to control another supernatural actor, the dangerous witch.

O my jaguar mat, did the villain perhaps come or not? Was he perhaps able to arrive? Was he perhaps able to arrive right up to my blanket? Did he perhaps raise it, lift it up?

This final incantation was to be recited when the sleeper awoke safely. He muses about what might have happened while he slumbered. Maybe nothing happened… or maybe a robber tried to attack, coming so close as to peek under the blanket at the defenseless sleeper, but was turned away successfully by the guardian spirits invoked the previous night. Either way, the speaker is safe and sound in the rosy light of dawn, alive to begin another day.

*****

Ruiz, . A. H., Andrews, J. R., & Hassig, R. (1984). Treatise on the heathen superstitions that today live among the Indians native to this New Spain, 1629. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp.81-82

A Few Aztec Riddles

Watching the Hobbit in theatres last weekend got me thinking about riddles. Not only are they amusing, but the figurative language and ideas contained within them can point to interesting tidbits of culture. I’ve pulled a few of my favorites from the Florentine Codex and included them below, in slightly more informal language. After each riddle and its answer I’ve added some of my own notes and interpretations of the concepts they nod to (the commentary is my own work, not that of Anderson and Dibble).

Q: What’s a small blue gourd bowl filled with popcorn?

A: It’s the sky.

Mesoamerican cosmology divides the universe into sky and heavens (topan) above, the earth’s surface like a pancake or tortilla in the middle (tlalticpac), and the underworld (mictlan) below. Though all three have their own distinct and separate characteristics, they interpenetrate to a certain degree, and this riddle hints at that in a playful manner. The gourd itself is a product of the earth and its underworld powers, doubly so as it’s a water-filled plant (and is often likened to the human head), as is popcorn. In fact, first eating corn is the moment where an infant becomes bound to the earth deities as it takes of their bounty and starts to accumulate cold, heavy “earthy-ness” within its being. It’s also the start of a debt to the earth and vegetation gods — as They feed the child, one day that child will die and return to the earth to feed Them. I covered some aspects of this idea in my Human Corn post, if you’re curious to read more.

Q: What’s the little water jar that’s both carried on the head and also knows the land of the dead?

A: The pitcher for drawing water.

The land of the dead is traditionally conceived of as a place dominated by the elements of earth and water, filled with cool, oozy dampness. Rivers, wells, springs, and caves were places where the underworld power was considered to leak through to the mortal realm. Not only did this power seep through to us, but we could sometimes cross through them to reach the underworld as well (the legendary Cincalco cave being one of the most famous of these doors). Thus, thrusting the jar down into a watering hole or a spring, breaking through the fragile watery membrane, was sending it into Tlaloc and Chalchiuhtlicue’s world in a way.

Q: What lies on the ground but points its finger to the sky?

A: The agave plant.

The agave plant, called metl in Nahuatl and commonly referred to as a maguey in the old Spanish sources, is a plant loaded with interesting cultural associations. Its heart and sap is tapped to produce a variety of traditional and modern liquors like pulque, octli, and tequila, linking it to the earth-linked liquor gods like Nappatecuhtli, Mayahuel, and even Xipe Totec and Quetzalcoatl in their pulque god aspects. Additionally, each thick, meaty leaf is tipped with a long black spine that’s much like a natural awl. This spine was one of the piercing devices used by priests and the general public alike to perform autosacrifice and offer blood to the gods. Lastly, the beautiful greenish-blue color of the leaves of some species (like the blue agave), is the special color traditionally associated with beautiful, divine things. Take a look at a photo of the respendent quetzal’s tailfeathers — they’re just about the same color as the agave.

Q: What’s the small mirror in a house made of fir branches?

A: Our eye.

The Aztecs strongly associated mirrors with sight and understanding. Several gods, most notably Tezcatlipoca (the “Smoking Mirror”), possessed special mirrors that would allow them to see and know anything in the world by peering into them. Some of the records we have from before and during the Conquest record that some of the statues of the gods had eyes made of pyrite or obsidian mirrors, causing a worshipper standing before them to see themselves reflected in the god’s gaze. In the present day, some of the tigre (jaguar) boxers in Zitlala and Acatlan wear masks with mirrored eyes, discussed in this post and video. One last point on mirrors — in many of the huehuetlatolli (ancient word speeches), the speaker implores the gods to set their “light and mirror” before someone to guide them, symbolizing counsel, wisdom, and good example. The comparison of eyelashes to fir branches is rather interesting, as it reminds me of the common practice in many festivals of decorating altars with fresh-cut fir branches. The two elements combine to suggest a tiny shrine of enlightenment, the magic mirror nestled in its fragrant altar like a holy icon.

Q: What’s the scarlet macaw in the lead, but the raven following after?

A: The wildfire.

I included this one simply because I thought it was exceptionally creative and clever. I’m pretty sure it would stump even a master riddler like Gollum!

*****

Sahagún, Bernardino , Arthur J. O. Anderson, and Charles E. Dibble. General History of the Things of New Spain: Florentine Codex. Santa Fe, N.M: School of American Research, 1950-1982, Book VI, pp.236-239.

Aztec Art Photostream by Ilhuicamina

Happy New Year’s! Instead of fireworks, let’s ring in the new year with a superb photostream from Flickriver user Ilhuicamina. This set is of exceptional quality and covers many significant artworks excavated from the Templo Mayor and safeguarded by INAH at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Take a look!

Quiquiztli: The Conch Shell Trumpet

It’s the ending of the old baktun and the dawning of a new one, and I’d like to greet both the new era and the return of the Sun on this Winter Solstice with the blowing of conch horns!

The Aztecs named the conch shell trumpet quiquiztli, and the musicians who played them “quiquizoani.” This is the instrument that Quetzalcoatl played to defeat the devious challenge of Mictlantecuhtli, the Lord of the Dead, and reclaim the ancestral bones of humanity at the start of the Fifth Sun. I have seen some speculation that the “mighty breath” blown by the Plumed Serpent to set that newborn Sun moving in the sky was actually a tremendous blast on a conch horn. It’s the trumpet the priests played to call their colleagues to offer blood four (or five) times a night in the ceremony of tlatlapitzaliztli, and also during the offering of incense, according to Sahagun in the Florentine Codex . Tecciztecatl, the male Moon God, is sometimes depicted emerging from the mouth of a quiquiztli. The sound of the instrument itself was considered by the Aztecs to be the musical analog to the roar of the jaguar. Like the twisting spiral within the shell, the associations are nearly endless, doubling back on each other in folds of life, death, night, dawn, and breath.

The quiquiztli appeared in two offerings at the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan (offering #88). One shell was found on Tlaloc the Rain Lord’s side (not at all surprising, given the overwhelming watery connotations of the instrument). A second one was found on Huitzilopochtli’s side of the manmade replica of Coatepetl. If you would like to actually hear one of these very trumpets being played, you can click HERE to visit the International Study Group on Music Archaeology’s page for these trumpets. You can directly download the MP3 recording by clicking HERE.

I also found a beautiful photograph of an Aztec or Mixtec conch trumpet (covered in intricate carvings) currently in the holdings of the Museum of Fine Arts here in Boston. If you’d like to view the photo and see their notes on the artifact, please click HERE. If you’d rather jump right to the full-size, more detailed image, click HERE instead.

Want to learn more about the trumpet and its uses in Mesoamerican cultures past and present? Head on over to Mixcoacalli and read Arnd Adje Both’s excellent 2004 journal article called “Shell Trumpets in Mesoamerica: Music-Archaeological Evidence and Living Tradition” (downloadable full text PDF). It gives a valuable introduction to the instrument in Teotihuacan, Aztec, and Mayan societies and includes numerous interesting photos and line sketches as a bonus. I couldn’t find a direct link to the article on his site, but I did find it on his server via Google. As a courtesy, the link to his homepage is here. There is some other interesting material relating to the study of ancient Mesoamerican music on there, so I recommend poking around.

What about South American cultures? I’m a step ahead of you — why not go here to read an interesting article on Wired about a cache of 3,000 year old pre-Incan shell trumpets found in Chavin, Peru? Includes recordings and photos.

Finally, if you’re curious for an idea of how the Aztecs and Maya actually played the quiquiztli, including how they changed the tone of the instrument without any finger-holes or other devices, you can view a demonstration by ethnomusicologist John Burkhalter below. If you noticed that the trumpeter in the codex image I embedded earlier has his hand slipped into the shell, you’ll get to see what that actually does when the horn is played in the video.

Aztecs In The Werner Forman Archive

Tonight I’ve decided to bring your attention to a major collection of photographs of Aztec and other Mesoamerican art, crafts, and architecture. It’s housed at the Werner Forman Archive in the United Kingdom. It’s a treasure trove of wonderful pictures of literally thousands of different objects and places around the world, including pictures relating to the Aztecs, Maya, Teotihuacanos, and other peoples of Central America.

Click HERE to enter the Archive and begin browsing or searching.

You can browse their Precolumbian section for photos covering both North and South American peoples, or you can try searching for Aztec, Maya, or more specific keywords. To give you a hint at how much there is to explore, the full Precolumbian section has 763 photos available online!

As they don’t appear to look kindly on people rehosting their images, and hotlinking is rude, I’ll just drop a few direct links here to some particularly interesting photos to get you started…

Click here to see a sculpture of Tlaloc, Lord of Storms and Tlalocan, in His Earth-lord guise.

Want to see a pectoral device in the shape of a chimalli (shield)?

How about Quetzalcoatl’s signature necklace, the wind jewel?

Joe Laycock & Santa Muerte

I’ve been keeping an eye on the alleged human sacrifices in honor of Santa Muerte (Saint Death) in Nacozari, Mexico, since the news first broke a bit over a week ago. Since the initial story hit, it’s been a rather vexing (if not surprising) slog through the misinformation and tedious sensationalism, with the usual suspects coming out of the woodwork to push a new version of the tired “Satanic Panic” trope. I’m pleased to inform however, that a friend of mine, Joseph Laycock, just posted a story regarding the killings on the Religion Dispatches. With his usual wit, Dr. Laycock deconstructs that bit of irritating nonsense, and provides a nice bit of work tracking how this meme is rapidly developing. I highly recommend popping by and giving it a read.

If you’re wondering why I’m taking a moment to post news relating to human sacrifices offered to a Catholic saint, you might want to swing by Dr. Laycock’s other article on Santa Muerte. Among other interesting data of note, he comments on the theory that Santa Muerte is a syncreticism of Catholicism with Mictlancihuatl (aka Mictecacihuatl), the pre-Columbian consort of Mictlantecuhtli and Queen of the Dead. (Her names translate literally as “Lady of the Land of the Dead” and “Lady of the Deadlands People,” respectively.) The first time I came across information relating to Santa Muerte, I had the exact same thought come to mind. Both entities appear as skeletal feminine figures draped in sacred garb. While Santa Muerte’s dress most obviously echoes a combination of Saint Mary (and by extension, the Virgin of Guadalupe, who is herself a syncretism of Tonantzin) and popular depictions of the Grim Reaper, her functions remind me far more of Mictlancihuatl. Both grim ladies have power over material blessings and fortunes, as well as life and death. This combination of dominion over material wealth and death is a signature of the Aztec earth/death deities (the powers of the earth and the force of death are inseparable in this cosmovision, when one gets to the root of it) such as Mictlancihuatl, Tonantzin, Cihuacoatl, and Tlaloc, among many, many others. The offering of blood and human life to Santa Muerte seems to hint that at least some others see this connection between the new saint and the ancient goddess, the tragic manifestation of this understanding in the case of the Nacozari murders aside.

With that said, I do encourage you to check out Dr. Laycock’s informative articles on Santa Muerte HERE and HERE, and give the ill-informed and sensationalistic tripe from non-experts floating around on the web a miss. Stay tuned for an upcoming post to stay with the subject of death while linking back to my prior post on the two major anthologies of Aztec poetry.

Astronomical Alignments at the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan, Mexico

In honor of the spring equinox, I’d like to share an interesting article by Ivan Šprajc that explores some theories regarding possible astronomical associations of the architecture of the Grand Temple. Mr. Šprajc is a Slovenian archaeoastronomy specialist with an interest in the ancient astronomical practices of the Aztec, Maya, and Teotihuacan peoples. This paper, “Astronomical Alignments at the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan, Mexico” is the result of the studies he conducted at the excavation site of the Huey Teocalli in Mexico City.

In this paper, Šprajc agrees with his predecessors Aveni, Calnek, Tichy, and Ponce de Leon that the Templo Mayor was indeed constructed to align with certain astrological phenomena and dates. This initial concept is partially based on some clues recorded by Mendieta that the feast of Tlacaxipehualiztli “fell when the sun was in the middle of Uchilobos [archaic Spanish spelling of Huitzilopochtli].”

The more traditional position, held by Aveni et al and supported by Leonardo López Luján in “The Offerings of the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan” (2006) holds that the festival’s beginning was marked by the perfect alignment of the sunrise between the two sanctuaries atop the Temple on the first day of the veintena according to Sahagun. To wit, Sahagun recorded that the festival month began on March 4/5 (depending on how you correct from the Julian to Gregorian calendar) and ended shortly after the vernal equinox.

Unlike his peers, Šprajc concludes that the festival of Xipe Totec was marked by the sun setting along the axis of the Teocalli. At that time, the sun would seem to vanish as it dropped into the V-shaped notch between the two shrines of Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli. His conclusion partially stems from a slightly different measurement of the orientation of the temple than the other archaeologists, and his preference for Mendieta’s dating of the start and end of Tlacaxipehualiztli, which would start right around the vernal equinox and then end on about April 4th.

Who do I think is correct? I think the jury is still out. Both the sunrises and sunsets were marked by the priests with copal offerings and music, and both were involved in the flow of various festivals, so we know for sure that the scholars and clergy of Tenochtitlan assigned significance to both. Given the issue of varying estimates of how much the Templo Mayor has settled into the soft soil of the remains of Lake Texcoco, and differing theories on how much the structure has warped due to intentional destruction and pressure from the layering of Mexico City on top, and it becomes hard to present a bulletproof argument for either side.

Šprajc presents some additional interesting possibilities for alignments with Mount Tlamacas and Mount Tlaloc nearby, and a potential method of tracking the movement of the sun that possesses regular intervals of 20 days (matching an Aztec month) and 26 days (two Aztec weeks) that are intriguing. However, I generally consider Sahagun more reliable than Mendieta, as his research methods were among the best at the time, and modern study has tended to vindicate his records over those of historians working at a greater remove in time after the Conquest. There’s also the issue that Šprajc seems to be quite outnumbered when it comes to support for his alignment, and some of those who disagree with him, like Leonardo López Luján, have devoted decades of their lives to studying the Templo Mayor specifically. I’d also like to close with the possibility that everyone could be wrong — the tendency to see astronomical alignments under every rock and bush that were never intended by the people they’re studying has plagued archaeology for a very long time, and in the end, it could be the case here as well. Regardless, the debate is interesting and well worth reading, and the journal article contains a number of useful photographs and diagrams of deep within the layers of the Templo Mayor that are rewarding in and of themselves.

To download a full-text PDF copy of the journal article for free from the Inštitut za antropološke in prostorske študije (Institute of Anthropological and Spatial Studies), please click HERE. Alternatively, you can read it on-line at Issuu in simulated book format straight from your web browser by clicking HERE.

As a bonus, I’ve embedded a beautiful video recorded by Psydarketo below. It’s footage of the sun rising and aligning in the central doorway of the sanctuary atop the Mayan temple at Dzibilchaltun on March 20th, 2011 — last year’s spring equinox. It’s a similar technique to what I discussed above at the Templo Mayor, except that the sun is framed in the doorway rather than in the V-shaped space between twin sanctuaries. Close enough to help give a picture of how things would have looked in Tenochtitlan, and wonderful to watch in its own right.

Courtesy link to the original video at Psydarketo’s YouTube page.

————————————————-

WorldCat Citation

Tigre Boxing In Acatlan: Jaguar & Tlaloc Masks

Up today is another video about the Mexican Tigre combat phenomenon I discussed a few weeks ago. This one shows a style of fighting practiced in Acatlan. Instead of rope whip-clubs as in Zitlala, these competitors duel with their fists.

Courtesy link to ArchaeologyTV’s page on YouTube for this Tigre combat video.

A particularly interesting feature of this video is the variety of masks. Not only do you see the jaguar-style masks, but you’ll also see masks with goggle eyes. Goggle eyes are, of course, one of the signature visual characteristics of Tlaloc, the very Teotl this pre-Columbian tradition was originally dedicated to. (And still is in many places, beneath the surface layer of Christian symbols.) If you look closely, you might notice that some of the goggle eyes are mirrored. The researchers behind ArchaeologyTV interviewed one of the combatants, who said that the significance of the mirrors is that you see your own face in the eyes of your opponent, linking the two fighters as they duel.

This idea of a solemn connection between two parties in sacrificial bloodshed was of major importance in many of the pre-Conquest religious practices of the Aztecs. It can be seen most clearly in the gladiatorial sacrifice for Xipe Totec during Tlacaxipehualiztli. During this festival, the victorious warrior would refer to the man he captured in battle as his beloved son, and the captive would refer to the victor as his beloved father. The victim would be leashed to a round stone that formed something of an arena, and given a maquahuitl that had the blades replaced with feathers, while his four opponents were fully-armed. As the captor watched the courageous victim fight to the death in a battle he couldn’t win, he knew that next time, he might be the one giving his life on the stone to sustain the cosmos.

Tigre Rope Fighting In Zitlala

Following up on last week’s post discussing the survival of Precolumbian gladiatorial combat in honor of Tlaloc in Mexico, I’ve got a video today that actually shows part of a Tigre whip match at Zitlala. Now that this activity has come to my attention, it’s something I’ll be watching for videos of in addition to Danza Azteca. It’s interesting getting to actually see the story behind the jaguar mask and contemplate the deeper meaning behind the fighting.

Courtesy link to ArchaeologyTV’s page on YouTube for this Tigre combat video.

In case you’re wondering, the special rope club used by Tigre fighters in Zitlala are called cuertas. The modern cuerta itself is actually a “friendlier” version of heavier rawhide and stone clubs used previously, which in turn were descended from stone and shell clubs used when the battles may well have been lethal. For obvious reasons, the present-day trend has been away from fatal contests, though the underlying meaning of giving of oneself to Tlaloc for a plentiful harvest endures today among those who remember.

Tlaloc In Zitlala

Came across an interesting photograph recently that’s quite interesting, as it shows an aspect of a Pre-Columbian ceremony still surviving today in Zitlala, Mexico.

Tigre Fighter With Whip & Jaguar Mask. Copyright 2008 by the Associated Press/Eduardo Verdugo. Used without permission.

Link to original photograph source.

Original Caption:

“A man dressed as a tiger carries a small whip made from rope in Zitlala, Guerrero state, Mexico, Monday, May 5, 2008. Every year, inhabitants of this town participate in a violent ceremony to ask for a good harvest and plenty of rain, at the end of the ceremony men battle each other with their whips while wearing tiger masks and costumess. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo)” [Cehualli’s note — “tiger” is a common mistranslation of “tigre,” when the context makes it apparent a jaguar or other large cat is meant.]

Now…there’s a lot more going on here that the photographer doesn’t get into in his note. Specifically, that this is a modern survival of traditional indigenous religious practices.

Why do I think this? Let me explain.

There’s a certain ancient god of rain in Mesoamerica who has traditionally been associated with jaguars… and that’s Tlaloc. In the codices, if you look carefully you can see that He’s always depicted with long, fearsome jaguar fangs. The growl of the jaguar resembles the rolling of distant thunder, and the dangerous power of such an apex predator fits the moody, explosive-tempered Storm Lord quite nicely. The jaguar as a symbol of Tlaloc is a very ancient tradition that appears across the whole of Central America, whether the god is being called Tlaloc, Cucijo, Dzahui, or Chaac.

The whip-club is another hint. Flogging has been done as part of rain ceremonies for Tlaloc for centuries (I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s symbolic of lightning). Additionally, though the photographer didn’t mention this, one knows what happens when people strike each other hard with whips like the one the man in the photo is shown carrying — you bleed. A lot.

In Prehispanic Mexico, one of the important rituals for Xipe Totec, the Flayed Lord, god of spring and new growth, is called “striping.” Striping involved shooting the sacrificial victim with arrows for the purpose of causing his blood to drip and splash on the dry earth below, symbolizing rain that would bring a good harvest. Similar rituals specifically devoted to Tlaloc were also done, and I wouldn’t be surprised if the gladiatorial combat done for Xipe Totec had the same basic idea in mind, sprinkling blood over the ground done to call the rain.

The next part is due to my good friend Shock and her impressive knack for research. While we were discussing this photo, Shock directed me to an excellent article about this phenomenon known as “Tigre Boxing” that still exists all throughout Mexico today. It even discusses this specific form of battling with whips in Zitlala that this photograph is of. I highly recommend checking it out, as it’s loaded with more information about the surviving practice of gladiatorial combat for rain, complete with many excellent photos of the jaguar masks, sculptures, and even videos of the combat!

A Penitential Rite Of The Ancient Mexicans

I have discovered online a very interesting classic journal article about Aztec autosacrifice by the esteemed Dr. Zelia Nuttall. Written in 1904, it lacks the benefits of recent scholarship, but it still remains a keystone work in understanding the specific form of autosacrifice that is bloodletting from the ears. Dr. Nuttall provides detailed description and discussion of the various specific forms of ear sacrifice, accompanied by extensive translation from numerous codices and photographs of pictorial depictions of this type of penance. If you are interested in learning more about how the Aztecs traditionally performed ear sacrifice, I strongly recommend following the link to read the article. Even better, as it is in the public domain, the full text is available to download as a PDF through Google Books!

Click here to go read “A Penitential Rite of the Ancient Mexicans” by Dr. Zelia Nuttall!

Some highlights of this article are discussions of the close association of ear autosacrifice with the gods Tezcatlipoca, Mixcoatl, Huitzilopochtli, and Quetzalcoatl. Of particular interest during this veintana of Quecholli is the description of a special type of autosacrifice attributed to Mixcoatl, the God of the Hunt. The article includes several forms of ear sacrifice linked to specific veintanas, including Quecholli and Panquetzaliztli. Additionally, it describes a sacrifice offered on the day Nahui Ollin, the daysign of the current Sun, the Sun Four Movement.

Also interesting is Dr. Nuttall’s analysis of the jaguar/ocelot imagery surrounding Tezcatlipoca and his connection to the constellation Citlal-Xonecuilli, which is known today as either Ursa Major or Minor (a little help on which one, Shock?). [Edit — It’s Ursa Major. Thanks, Shock!] Instead of a bear, the Aztecs saw the constellation as a jaguar and a symbol of Tezcatlipoca. It reminded them of the time when Tezcatlipoca, acting as the First Sun, was chased from the sky by Quetzalcoatl and descended to Earth in the form of a great jaguar to devour the giants, the first people. That is why the constellation seems to swoop from its peak in the sky down to the horizon, reenacting this myth every day in the night sky.

My only irritation with this article is a few points where the good doctor strays from proper anthropological neutrality to make disparaging comments about the practice of autosacrifice, and to congratulate the Spaniards on stamping it out. I’ll admit it, I do derive a certain sly pleasure in discussing it here so that it’s not forgotten!

Study Of A Contemporary Huaxtec Celebration At Postectli

I came across an interesting article by Alan R. Sandstrom on FAMSI the other night. It is a summary of his observation of a modern Huaxtec ceremony honoring one of the Tlaloque, a rain spirit named Apanchanej (literally, “Water Dweller”). This festival took place in 2001 on Postectli, a mountain in the Huasteca region of Mexico.

A bit of background — the Huaxtecs are an ancient people, neighbors of the Aztecs. Like the Aztecs, they spoke and still speak Nahuatl, making them one of the numerous Nahua peoples. To this day they still live in their traditional home, one of the more rugged and mountainous sections of Mexico. They have retained more of their indigenous culture than some of the other nations that survived the Conquest due to their remoteness and the rough terrain that inhibited colonization. This includes many pre-Conquest religious traditions, even some sacrificial practices.

To read the short article summarizing Sandstrom’s experiences at the ceremony:

If you would like to read the article in English, please go HERE.

Si desea leer el artículo en español, por favor haga clic AQUI.

Some Highlights Related To Modern Practices

This article includes discussion of several details of particular interest to those interested in learning from the living practice of traditional religion. Of special note are photographs of the altar at the shrine on Postectli, including explanation of the symbols and objects on it (photograph 12). Also, the practice of creating and honoring sacred paper effigies of the deities involved in the ceremony is explored in some depth. Paper has traditionally been a sacred material among the Nahua tribes, and paper representations of objects in worship is a very old practice indeed. Additionally, there is some detail on tobacco and drink offerings, as well as the use of music and the grueling test of endurance inherent in the extended preparation and performance of this ritual.

Contemporary Animal Sacrifice

A key part of the article’s focus is on the modern practice of animal sacrifice and blood offerings that survive among the Huaxteca today. These forms of worship have by no means been stamped out among the indigenous people of Mexico, as Sandstrom documents. (Yes, there are photographs in case you are wondering — scholarly, not sensationalistic.) Offering turkeys is something that has been done since long before the Conquest, and from what I have read they remain a popular substitute for humans in Mexico. It’s fitting if you know the Nahuatl for turkey — if I remember right, it’s pipil-pipil, which translates to something like “the little nobles” or “the children.” If I’m wrong, someone please correct me, as I don’t have my notes on the Nahuatl for this story handy at the moment. They got that name because in the myth of the Five Suns, the people of one of the earlier Suns were thought to have turned into turkeys when their age ended in a violent cataclysm, and they survive in this form today. I doubt the connection would have been lost on the Aztecs when offering the birds.

Closing Thoughts

To wrap things up, Sandstrom’s article was a lucky find and is a valuable glimpse into modern-day indigenous practice . I strongly recommend stopping by FAMSI and checking it out, as my flyby overview of it can’t possibly contain everything of interest. On one last detail, I strongly encourage you to read the footnotes on this one — a lot more valuable info is hidden in those.

Aztecs At The British Museum

In the spirit of the aphorism “a picture is worth a thousand words,” I recommend stopping by the British Museum’s Aztec collection online. They have available 27 photographs (well, 26 if you ignore the crystal skull that’s been proven to be a hoax) of beautiful Aztec and Mixtec artifacts. Among them are statues of Quetzalcoatl, Tezcatlipoca, Mictlantecuhtli, Tlazolteotl, Tlaloc, Xochipilli, and Xipe Totec, as well as a rare mosaic ceremonial shield, a turquoise serpent pectoral, and a sacrificial knife. The images are thought-provoking and intense, as these objects speak wordlessly the vision of the Nahua peoples without Colonial censorship.

Click HERE to visit the British Museum’s Aztec Highlights.

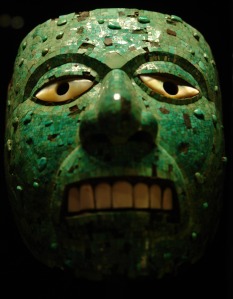

As a bonus, I located an excellent photograph of a jade mask of Xiuhtecuhtli, God of Time and Fire, which is a part of the British Museum’s collection but is not on their website. Thank you Z-m-k for putting your fine photography skills to work on this worthy subject material and for your kindness in sharing it under the Creative Commons Attribution Share-Alike 2.5 License.

Aztec Prayers & Poems Collected By Alarcon

I came across a lovely little hoard of traditional Aztec poems, prayers, and songs the other night. These were originally recored in Ruiz de Alarcon’s 1629 work, Tratado de las supersticiones y costumbres gentílicas que oy viven entre los indios naturales desta Nueva Espana, commonly referred to as “Treatise on Heathen Superstitions” for short in English. For example, he’s posted prayers for safe travel, for love, and even a myth in song about Xochiquetzal and the Scorpion. Professor Joseph J. Fries of Pacific Lutheran University is the person who has generously posted these precious literary treasures, and he includes a bit of commentary as well. Thank you, Dr. Fries!

The Origin Of Corn

I think it’s time for retelling another myth, Cehualli-style. Chronologically, this one follows immediately after the tale about how Quetzalcoatl recovered the bones from Mictlantecuhtli in the great cycle of creation myths of the Aztecs. In this story, the age of the Fifth Sun has just begun, and the humans have just been brought back to life. So now there’s dry land, light, and living people again, but the recreation of the world isn’t done yet, for the people have nothing to eat. The legend of the Origin of Corn shows how the Teteo solve this last problem and complete the restoration of Earth.

The Origin Of Corn

As told by Cehualli

The Teteo stepped back to admire their work. They looked up to the sky and saw the Sun, radiant and majestic as He moved across the turquoise-blue sky. They looked down below and saw the jade-green earth, full of life, bounded on all sides by the Sacred Waters of the sea. They saw the newly-reborn humans, gazing back at Them with awe and gratitude for what They had done. Then the gods realized that Their work wasn’t done yet.

“We’ve brought the people back to life, but it will all be a waste if they don’t have something to eat! Mictlantecuhtli and Mictlancihuatl will Themselves die of laughter if the bones They covet so badly return to Them this quickly,” said Xolotl, shaking His canine face in dismay.

“The different kinds of food that we’d given the people in the previous four Suns won’t be right for these, for these are true humans,” said Tlaloc, the Lord of Rain, His voice a rumbling growl like a jaguar. “We need to find the real corn for our new servants.” His words were correct, for in the past ages of the world, only lesser plants that mimicked corn existed, just like how real humans weren’t yet made.

Quetzalcoatl stroked His feathery beard, deep in thought, His eyes downcast. Right when He was about to speak, His gaze fell upon a tiny red ant… which was carrying a single kernel of corn. “I think We may have just found the true corn…” And with that, He descended back to the mortal world, leaving Tlaloc and the rest of the gods to watch what happened next.

“Wise ant, where did you find this corn?” Quetzalcoatl politely asked the tiny creature. The ant looked up at the god, surprised to see a Teotl talking to her, but she didn’t answer. Instead, she just kept on walking, not relaxing her grip on the corn at all. Undeterred, Quetzalcoatl turned himself into a black ant and followed after her.

At last they came to the foot of a soaring mountain. The red ant walked up to a tiny crack at the base and gestured to it with her antennae. “This is the Mountain of Sustenance. Corn, beans, chili peppers, and everything else that’s good to eat is stored inside.” Quetzalcoatl thanked her for her guidance and entered the mountain. Once inside, He gathered up some corn and brought it back to the heavenly world of Tamoanchan.

The rest of the gods were delighted by Quetzalcoatl’s discovery. “Our servants will live after all. Quick, let’s give them the corn!” They said. Quetzalcoatl took the maize and chewed it until it was soft, then gently placed it in the mouths of the newborn humans who were weak with hunger. Strength returned to the people, who praised the gods.

Meanwhile, Tlaloc and His ministers, the Tlaloque, were walking around the Mountain of Sustenance, examining it. “Now, what should We do with this?” He murmured to Himself, a hint of greed in His thunderous voice.

Quetzalcoatl broke open the mountain and admired the bounty within. “We’ll give it to the people so they’ll thrive and worship Us.”

Tlaloc frowned, His long jaguar teeth showing frighteningly. “No, I think I have a better idea.” And He suddenly ordered the Tlaloque to scoop up the food inside, and together They spirited it back to Tlaloc’s own realm, Tlalocan. Tlaloc admired His prize, running His fingers through the piles of food. “Why should I just give the humans all this for free? I should get something in return. I’ll water the earth and make the food grow, but only if they worship Me and offer blood. If they don’t, then I’ll send drought and storms until they keep their end of the bargain again.”

And that is how the right kinds of crops for humans came to be.

Danza Azteca — Quetzalcoatl’s Descent to Mictlan

Here’s the video of the Aztec dance performance of part of the story of Quetzalcoatl’s descent to Mictlan, the Land of the Dead, to retrieve the precious bones so that humans can live again. It’s a nighttime performance, which is a perfect fit for the setting. Mictlan was described as a place of perpetual darkness, coldness, and night. The lighting is mostly from the bonfire and a few lamps, so it’s very moody looking and the shadows and light accentuate the motions and costumes of the danzantes.

Update 4/21/2008:

Quetzalcoatl is portrayed by the dancer in the birdlike, beaked mask who’s carrying the serpent, while Mictlantecuhtli is played by the dancer with the lion’s-mane-like headdress with a skull in the center of the fan of feathers. Mictlantecuhtli’s servants are creatively portrayed by children in skeletal costumes. You’re probably wondering “Why kids? That’s not scary!” I think they’re echoing the myths that portray Tlaloc’s helpers, the Tlaloque, as miniature versions of the goggle-eyed Rain God. If Tlaloc’s assistants are mini-Tlalocs, then why not have the Lord of the Dead’s be miniature Mictlantecuhtlis? Either way, it’s a nice casting choice.